|

TECHNOLOGY ⸜ digital recorders 3M DIGITAL AUDIO MASTERING SYSTEM

|

|

TECHNOLOGY

Text by WOJCIECH PACUŁA |

|

No 256 September 1, 2025 |

In 1978, the American company 3M – Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company – presented its own digital tape recorder. It was actually something more – an entire recording and mastering system consisting of a 32-track multi-track tape recorder (16-bit, 50 kHz) with 1-inch tape and a 4-track, 1/2-inch mastering recorder. These tape recorders went down in music industry history as the basis for many rock music recordings. But there’s more. It was also one of the best machines of its kind. Developed in collaboration with the BBC, it was ahead of what Mitsubishi and Sony would present a few years later with their tape recorders operating in the ProDigi and DASH systems, respectively. The 3M system was also the first tape recorder of its kind with a fixed head, which was a significant change from the two earlier digital tape recorders by Denon and Soundstream.

⸜ One of the few available photos of the 3M Digital Audio Mastering System comes from press materials and can also be found in the thick user manual. You can read more about those technologies in the summary entitled Digital recording technology 1971-2023 → HERE. ▌ It all began with a tape 3M, an American conglomerate operating in the industrial, occupational safety, and consumer goods industries, known, for example, for its adhesive tape known as Scotch tape, is the manufacturer that developed the key compound used by DuPont to create Teflon. In 1947/48, it developed a black, oxidized tape with a plastic backing, which evolved from paper tape. According to the Museum of Magnetic Sound Recording website, it was magnetic tape called Scotch Magnetic Tape No. 100, designed for the Brush tape recorder, one of the first American-made tape recorders. Tapes of this type were already known at the time, but the technology still needed improvement. Historically, the first was the German company BASF (Badische Anilin- und Sodafabrik), specializing in the production of plastics. From 1924, its I.G. Farben division in Ludwigshafen produced an extremely fine carbonyl iron powder for the production of induction coils for telephone cables. The company's ability to produce extremely fine dispersions came from its experience in the production of dyes, and, as stated on the manufacturer's website, “ultimately, new plastics are suitable as a carrier.” The first 50,000 meters of magnetic audio tape were delivered to the electronics corporation AEG in 1934. A year later, AEG unveiled the first K1 tape recorder (Magnetophon) to the public, which was based on magnetic tape produced by BASF. They caused a sensation at the Berlin Radio Fair in 1935 and quickly found their way into the radio stations of the Third Reich, becoming a tool of Nazi political propaganda. But let's return to the United States. After two units of the Magnetophone, as AEG christened its machines, were brought to the US after World War II, the officer who tracked them down, Jack Mullin, used them as the basis for his own designs, which he demonstrated to a branch of the Institute of Radio Engineers in San Francisco in May 1946 and later at MGM Studios in Hollywood in October of the same year. An entry in Wikipedia reads:

The Ampex A200 became the first professional reel-to-reel tape recorder produced in the US and marked the beginning of a whole new chapter in the history of sound recording. As we read in Friedrich Engel and Peter Hammar's work entitled A Selected History of Magnetic Recording, this sparked a race involving dozens of American companies to build the best or cheapest, largest or smallest professional and consumer tape recorders. And, as we already know, tape recorders needed the right tape.

⸜ Information available on the A Comparison in Sound. Digital vs Analog Recording sampler were supposed to convince sound engineers As early as 1944, Otto Kornei of Brush Development Company wrote to Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Co (3M) asking if they would be interested in developing a thin non-metallic tape coated with an emulsion containing ferromagnetic powder. As we read in Charles L. Alden's book review 3M – Magnetic Media Maker, a history of the first four decades (1944...1985), available on the AES website → HERE, 3M replied that it would like to try, and thus a great American industry was born:

The Mincom division of 3M not only developed tape for tape recorders, but also designed its own tape recorders. It sold several models of magnetic tape recorders for use in data collection systems and studio sound recording. An example of the latter is the M79 recorder, one of the manufacturer's most important models. Although Ampex remained the pioneer in the implementation of multi-track tape recorders, it was 3M that developed the 8-track tape recorder used by renowned sound engineer Wally Heider. He is known as the “father” of the sound on albums by Jefferson Airplane, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, Van Morrison, the Grateful Dead, Creedence Clearwater Revival, and Santana. However, 3M had greater ambitions than just “keeping up” with Ampex – it wanted to be the leader. ▌ A shift towards digital technology AS JOE CLERKIN, whose article was published in Electronics & Music Maker magazine in 1982, points out, the recording industry played an important role in improving sound quality. It's hard to believe, he wrote, that “almost twenty years ago, George Martin was recording the Beatles on four tracks and in mono!” The milestone for the recording world was, of course, the advancement of multi-track recording in the late 1960s, with most of the pioneering work, in his opinion, done by 3M.

⸜ The first editions of Appalachian Spring by Aaron Copland and Three Places in New England by Charles Ives were released in 1978 by Studio 80 – the photo shows the 1983 Pro-Arte Digital reissue with Digital logo The M79 tape recorder we mentioned was the workhorse of many recording studios around the world in the 1980s. According to Clerkin, multi-track recording – in which M3 machines were an important element – was a milestone in the music industry. Among its advantages, he cites above all improved creativity: “once the basic tracks were recorded on tape, you could play around with them endlessly – mixing and remixing until the producer was satisfied with the result.” The multi-track revolution, because there is no other way to describe it, also had its opponents. Let us recall that Rudy Van Gelder was the biggest supporter of two-track recordings. The technical problem he struggled with throughout his career was tape noise. That's why he maximized the signal as much as possible, which increased the signal-to-noise ratio, but he didn't want to introduce the next generation of tape into the recording chain; more → HERE. While monophonic and then stereophonic tape was considered a “master” tape (→ 1), and it was used to make a copy without splicing (→ master 2), and then copies for the pressing plant (→ master 3), multi-track recordings required one more step – mixing to two channels. What is more, the noise of tape recorders with more tracks was significantly higher. This was because each of the narrow “ribbons” with the recorded signal had a much smaller area of ferromagnetic material. Incidentally, this is one of the reasons why many early mono recordings sound so good – the signal had the entire width of the ¼” tape at its disposal. And even if 24-track tape recorders used 2" tape, it is easy to calculate that each track had three times less surface area than in a stereo tape recorder and six times less than in a mono version. However, the revolution could no longer be stopped. This was particularly true in popular music genre. As Susan Schmidt Horning writes, rock musicians considered everything that had come before them to be outdated and boring. They also wanted to record differently, experiment more with effects, which was limited or even impossible in the world of multiple tracks. On the other hand, she adds, the extended recording time with tape recorders resulted in a much less spontaneous effect, which caused the energy to dissipate.

⸜ Although Wikipedia states that this recording was pressed from a direct-to-disc session, the information on the album insert indicates otherwise. Horning recalls Al Smith in this context. The recording studio giant, who died in 2021, was an American recording engineer and producer. He won twenty Grammy Awards for his work with Henry Mancini, Steely Dan, George Benson, Toto, Natalie Cole, and Quincy Jones. His clients also included Frank Sinatra with Duets and Ray Charles with Genius Loves Company, and he also recorded some of Diana Krall's albums. Horning quotes his opinion on multi-track recordings:

A change in the perception of multi-track recordings came in the mid-1960s, and nothing could stop this wave. From then on, the studio became a place for recording monophonic sound elements, which were then mixed together into a whole. After reaching twenty-four tracks, producers began to think about thirty-two, but this never made it past the wishful thinking and prototype stage. Otari produced a 32-track, 2-inch (51 mm) MX-80 tape recorder, of which only a few units were made, and prototype machines produced by MCI in 1978, using 3" (76 mm) tape for 32 tracks, never went into production. The studios were dominated by 24 tracks, which could be duplicated by connecting two such tape recorders to get 47 channels (one was used for synchronization using SMPTE code) – this is how, for example, the Depeche Mode’s Violator (Mute, 1990) was recorded. Although from today's perspective, when we are familiar with recorders such as ADAT from 1991 or RADAR from 1993, and above all DAW computer recorders with Pro Tools (like ADAT, also from 1991), offering dozens and hundreds of tracks, it is precisely this “lust for tracks” that may seem to be the main reason for the emergence of digital tape recorders, but the reality is quite different. For years, they lagged behind analog tape recorders in terms of the number of tracks.

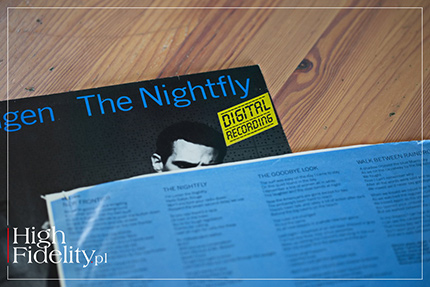

⸜ The cover of The Nightfly features a sticker with information about digital origin of the recording Let us recall that the first 24-track recorder was presented in April 1969 and it was the Ampex MM-1000 tape recorder. And although 16-track recordings remained the standard for several years, studios slowly began to switch, forced by bands wanting to work with as many tracks as possible. For years, EMI used older equipment, squeezing the most out of it: Let It Be was recorded on a 4-track Studer J37 (1970). In the mid-1970s, however, 24-channel tape recorders became the standard tool in most large recording studios. An interesting fact: in the studio of the Polish record label Tonpress, opened in the early 1980s, they used Studer A-80 16-track tape recorder. It was purchased specifically in this configuration, and according to the musicians' recollections, the buyer wanted it because it had lower noise than its counterpart with eight more tracks. No one understood this at the time, and for years, perhaps even to this day, the opinion persisted that it was a mistake. As we said, musicians and producers of popular music saw the tape recorder as just another instrument, and the more tracks it had, the more versatile it was, and therefore the better. And yet it was clear that from a technical point of view, it was the better choice. The reign of the twenty-four tracks lasted for twenty years. We read:

The end of this analog bonanza came with digital recorders. But not right away and with great resistance. Samantha Bennett says that, on the one hand, digital tape recorders were extremely expensive, which meant that few studios could afford them, and on the other hand, the first wave of devices, i.e. tape recorders from Denon and Soundstream, had two, four and eight tracks and eight (Soundstream); Denon developed a method of synchronizing two tape recorders, which allowed to use 16 channels. However, this was 1978, when 24-channel analog machines had been the new reality in studios for almost a decade. |

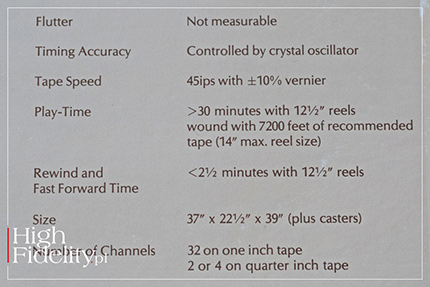

⸜ The insert for Fagen's album also includes information that this is a digital recording, with the emphasis on “entire recording”. The emergence of digital recorders and their development was motivated by something other than the amount of tracks. It was about the aforementioned noise and distortion. Engineers have been fighting them ever since they started recording sound, and each successive generation of devices was supposed to help reduce them. That is why highly problematic noise reduction systems, whether Dolby, dbx or other manufacturers, were so quickly adopted. In this respect, even the most primitive digital recorder beat analog ones hands down. ▌ 3M Digital Audio Mastering System I HOLD IN MY HANDS A RARE RELEASE, a unique item, to say the least. I am talking about the demo album A Comparison in Sound. Digital vs Analog Recording, released in 1978 by 3M Company (S80-1515). Each side of the vinyl record, prepared by Studio 80, contains two tracks – one recorded on the company's top-of-the-line M79 mastering tape recorder (2 tracks, 15 IPS), but an analog one, and the other using a digital tape recorder. The release is unassuming and served solely for promotional purposes and to demonstrate the superiority of the new digital recording and mastering system. However, since it was intended for sound engineers rather than consumers, it was prepared with great care and attention to detail. The light brown cover features a dark brown drawing of a 3M Company digital tape recorder, with the most important features of the recording listed below – the recorder, instrument, recording location, and microphones. A much more detailed description can be found on the second side. There, the company has published the full technical specifications of the new digital tape recorder, as well as measurement charts, which are intended to leave no doubt that potential customers, i.e. recording studios, should immediately switch to the new devices. At least, that's how I imagine it. Even though the price was prohibitive: $150,000 for the system, of which $115,000 was for the 32-track tape recorder and $35,000 for the 4-track tape recorder. The technical specifications provided by the manufacturer indicate very low intermodulation distortion, low crosstalk and, above all, low noise. The signal-to-noise ratio was > 90 dB. This does not seem as impressive as one might expect. Although the analog M79 tape recorder compared to it was capable of recording a signal at -68 dB, i.e. with significantly higher noise, the use of Dolby SR (Spectral Recording) noise reduction improved this result by as much as 28 dB. Theoretically, it was even lower than in the digital system. The thing is that every analog copy means 3 dB more noise. With classic recordings in the 4-6 generation range, this resulted in 18 dB or more of additional noise. Digital copies did not produce any noise. The second thing is that the cascaded use of Dolby SR or Dolby A systems significantly altered the sound. This was especially true because these analog circuits had to be tuned each time, which was usually forgotten. They sounded different when turned on, different when warmed up, and different again in the evening. Expander/compander noise reducers still have both supporters and ardent opponents today. The digital tape recorder freed us from these problems.

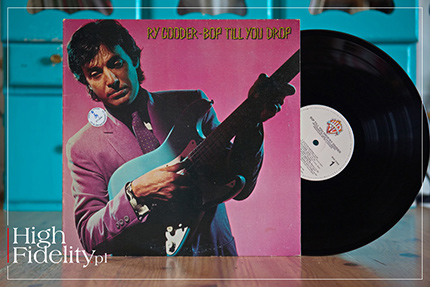

⸜ Cooder’s album was the first album recorded entirely digitally, but in the traditional multi-track manner How did a manufacturer of magnetic tapes, and more broadly, an American corporation involved in the manufacture and sale of a wide range of products, including plastics, abrasives, electronics, and pharmaceuticals, offering a total of over 55,000 products, one of the 30 companies indexed by the Dow Jones Industrial Average become a part of the story of digital recorders? As it turns out, it had ambitions to revolutionize the way sound was recorded and, at the same time, make money both on the “hardware” side by selling tape recorders and on the “software” side by offering tapes for them. The Mixonline magazine begins its article on the technology acquired by 3M Company, formerly known as Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company, as follows:

According to Thomas Fine, the Research Department of the BBC, a British broadcasting corporation wholly owned by the state, developed a 2-channel PCM recorder in the early 1970s. The device never made it past the prototype stage, but some of the technology was later sold under license to 3M. The latter presented its system in November 1977 at the AES convention in New York.

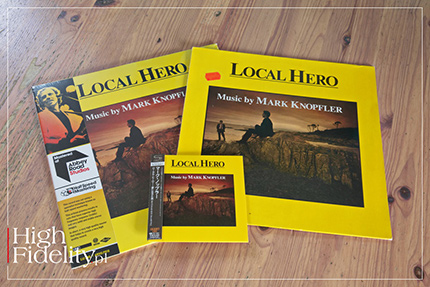

⸜ Local Hero has an interesting history – until recently, it was only known from a U-matic master tape; as it turns out, it was recorded on a JVC M3 tape recorder and mastered onto two internal tracks on a multi-track tape.j The complete recording and mastering system included two tape recorders – a 32-track recorder and a four-track mastering tape recorder, which could also operate in stereo mode (four tracks were designed for quadraphonic releases). Both decks operated at a speed of 45 ips, offering 30 minutes of recording time with a 12.5-inch reel with a length of 7,200 feet or 45 minutes with a 14-inch reel with a length of 9,600 feet. The system also included a controller that allowed tracks to be overdubbed and edited without loss. The system allowed previewing of edits, with the ability to move the tapes back and forth through the edit point for refinement before approval. Mixonline points out that perhaps the most interesting aspect of the 3M system was its A/D and D/A conversion scheme. Since, as we read, there were no true 16-bit converters available, separate 12-bit and 8-bit converters were combined to achieve 16-bit processing. This is not true – the Soundstream tape recorder presented in 1976 used Analogic MP8016 16-bit A/D converters with a sampling frequency of 50 kHz. So it must have been something else, but what – we don't know. Please note two values: the sampling frequency of 3M tape recorders and the number of tracks on the tape recorder. The first value, 50 kHz, seems to be a direct reference to Soundstream devices, which at the time was used for a lot of recordings, mainly classical and jazz music. There seemed to be a consensus that this was sufficient to provide full bandwidth audible to the human ear, with a margin allowing for the use of less intrusive, gentler anti-aliasing filters. In turn, thirty-two tracks were a nod to artists associated with the rock and pop music scene. Let us remind you that Denon tape recorders offered eight tracks and sixteen after synchronization, while Soundstream offered only four. And yet twenty-four channels were the norm for large studios at the time. No wonder, then, that this 32-channel scheme was later picked up by Mitsubishi and used in its ProDigi digital tape recorders. Fine writes bluntly: “The 3M system was aimed at the world of professional multi-track recording, which was typical of top rock and roll albums.” Although in 1978 the 3M system was a year away from actual availability, engineer Tom Jung, then at Sound 80 studio in Minneapolis and later associated with DMP Records, agreed to beta test prototypes of 3M's stereo tape recorders, using them as a backup system during direct-to-disc LP recording sessions. These machines had a sampling frequency of 50.4 kHz, two channels, and 16-bit recording depth. Which brings us back to the Soundstream system. In the summer of 1976, it was used for parallel recording of the Santa Fe Opera's production of The Mother of Us All with music by Virgil Thomson and lyrics by Gertrude Stein. The recording was so well received that a digital version was ultimately released on CD rather than analog record. It was the first digital recording session in America. In an interview with Audio Magazine in 1994, recording director Jerry Bruck recounted the first test recording with the Soundstream system.

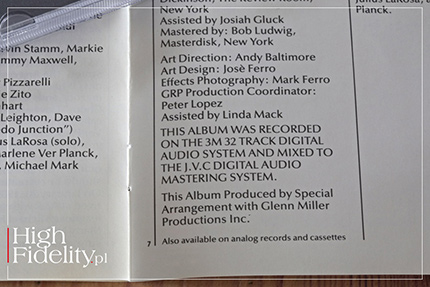

⸜ One of the first CDs recorded and remaster digitally – GRP label and The Glenn Miller Orchestra In The Digital Mood from 1983 Tom Stockham contacted him and asked if he could run his Soundstream system in parallel with the recording for testing purposes. Bruck agreed and set up the line from the New World Records mixing console for Soundstream in Santa Fe. Bruck recalls:

It was similar with the 3M tape recorders at Sound 80. The machine was nicknamed “Herbie” in honor of Sound 80 co-owner Herb Pilhfer. According to several participants, the recording session, which took place in June, featured the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra conducted by Dennis Russell Davies, performing Aaron Copland's Appalachian Spring and Charles Ives' Three Places in New England. The session was to be recorded directly to disc, with a prototype 3M used as a backup recorder. Fine writes:

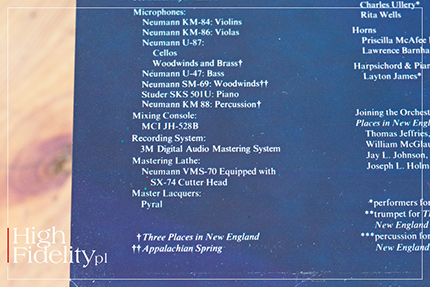

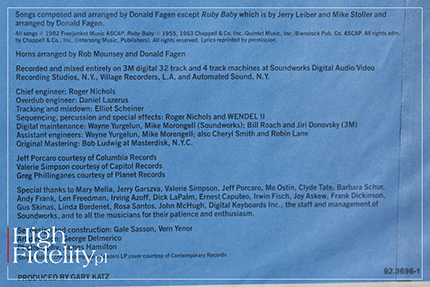

Digital session tapes were rated higher than direct-to-disc lacquers by sound engineers and producers. As a result, they were selected and in December 1978 the first commercial albums recorded using the 3M system were released: Flim & The BB's, by the jazz group Flim & The BB's, and Aaron Copland's Appalachian Spring, performed by the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra. The latter was nominated for three Grammy Awards, winning in the category of best chamber music performance. These recordings were made, let us recall, on experimental stereo tape recorders, which were soon dismantled. It is therefore impossible to read the tapes recorded on them, and the only witnesses to those recordings are analog records. The first dual-machine 3M systems were installed in early 1979 at Sound 80 and at A&M Studios in Los Angeles, Record Plant and Amigo Studios, owned by Warner Bros. Among the notable early pop releases recorded on the 3M system were Ry Cooder's Bop Till You Drop (with Lee Herschberg as sound engineer) and Donald Fagen's The Nightfly (with Roger Nichols as sound engineer). Cooder's album was the first fully digital album recorded in the traditional multi-track manner used in most popular/rock/jazz albums since the 1960s. Produced by Cooder and Lee Herschberg, it was recorded at Northern Hollywood Studios in California and released by Warner Brothers.

⸜ Usually, a full 3M mastering system was used – in this case, only its multi-track tape recorder, and the master was made on a JVC U-matic two-track recorder. In 1981, these machines also arrived in Europe and found their way to Polar Studios, owned by ABBA musicians Björn Ulvaeus and Benny Andersson, as well as the band's manager Stig Anderson, owner of Polar Music. It was here that the band's last “canonical” album, The Visitors (Michael B. Tretow as sound engineer), was recorded. This album is considered the first digitally recorded album to be released on Compact Disc. Thus, the world of analog recordings began to fade into the past. ▌ Summary FROM TAPE TO EXPENSIVE DIGITAL RECORDING SYSTEMS – the progress made by 3M is impressive. These weren't the first tape recorders of this type, but they were the first to offer so many tracks and such ease of editing. While Denon and Soudstream systems were largely “assigned” to classical and jazz music, the 3M system was designed with rock and popular music in mind. As listening to early albums recorded using the 3M system shows, these were some of the best machines of their kind. Even their later rivals, Mitsubishi and Sony, the latter of which won the entire race, were not quite able to replicate the sound offered by American tape recorders. How did those recording sound like? – We will try to answer this question in the following sections of the article, listening to the following albums: A Comparison in Sound. Digital vs Analog Recording, Aaron Copland, Charles Ives Appalachian Spring/Three Places In New England, The Glenn Miller Orchestra The Digital Mood, Christopher Cross Christopher Cross, Ry Cooder Bop Till You Drop, Donald Fagen The Nightfly, Mark Knopfler Local Hero and ABBA The Visitors. ● ▌ Bibliography → 1934 / Magnetic Audio Tape, → www.BASF.com, accessed: 4.02.2025. |