|

TECHNOLOGY ⸜ digital recorders DIGITAL RECORDING TECHNOLOGY

It all started in January 1971 with the world's first LP with digitally recorded material. In a long chain of successive recorders - among DENON Digital, SOUNDSTREAM, 3M, ProDigi, DASH, ADAT, RADAR - DAW, or DIGITAL AUDIO WORKSTATION, is the latest development. The development has lasted for more then 50 years. |

|

TECHNOLOGY ⸜ digital recorders

text WOJCIECH PACUŁA |

|

No 226 March 1, 2023 |

» DAW • DIGITAL AUDIO WORKSTATION is a part of the series of articles discussing digital sound recorders: ⸜ Denon Digital PCM | SOUNDSTREAM | SONY DASH → HERE⸜ MITSUBISHI PRODIGI ˻ Pt. 1 ˺ → HERE, ˻ Pt. 2 ˺ → HERE, ˻ Pt. 3 ˺ → HERE ⸜ ALESIS ADAT ˻ Pt. 1 ˺ → HERE, ˻ Pt. 2 ˺ → HERE, ˻ Pt. 3 ˺ → HERE |PL| ⸜ RADAR ˻ Pt. 1 ˺ → HERE, ˻ Pt. 2 ˺ → HERE, ˻ Pt. 3 ˺ → HERE ⸜ DAW ˻ Pt. 1 ˺ → HERE, ˻ Pt. 2 ˺ → HERE, ˻ Pt. 3 ˺ → HERE THE STARTING POINT FOR ME WAS the same as for most "High Fidelity" readers in their search for better sound: curiosity. I knew the sound of albums recorded by Denon on its digital tape recorders (PCM Digital), I was also aware of the uniqueness of Soundstream recordings. So I wanted to understand why these early, from today's point of view even primitive, methods of sound recording produced such a good effect, why they sounded so great.

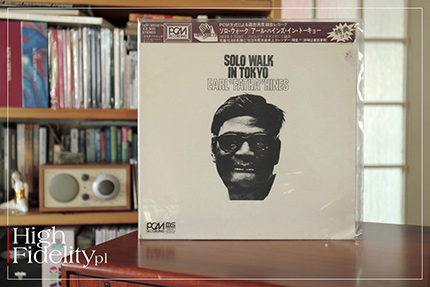

⸜ Great album by EARL "FATH" HINES Solo Walk in Tokyo, recorded on an eight-channel Denon DN-023 digital tape recorder, with a sampling frequency of 47.25 kHz and a word length of 13 bits. The article in question was created as an independent "entity". I had no plans to develop this topic, because it seemed to me that by learning the history of these two systems, I would exhaust it. Oh how wrong I was! (so will I exclaim so melodramatically). Although I could have guessed it, I was surprised to realize the richness of the subject matter in question and the far-reaching implications which the vast majority of professionals - producers, sound engineers, musicians and journalists - as well as audiences music, don't know about. As it turned out, digital technology, in its subsequent versions, changed the music industry itself, the way recordings, and even compositions are constructed, bringing many new music genres to life. PAUL THÉBERGE in the article The Sound of Music: Technology Rationalization and Musical Practice said that "technological innovation in this sense is not only a response to the needs of musicians, but also a driving force that musicians must get used to" . So it became clear that the dichotomy DIGITAL ↔ ANALOG, with its internal tensions and almost ritual hostility of individual groups of audiophiles, is something much, much, much more important than the issue of sound as such. It surpasses the reductionist approach nurtured in our industry and boils down to a primitive - please forgive me - comparison of "analog" and "digital". It’s just that at the end of the 1960s, when the first working prototypes of digital recorders were developed, no one thought about it. The goal was the same as with all previous revolutionary changes in the ways of recording, whether electrifying the track or presenting an LP: improving the quality of recorded sound. In this case, it was about eliminating the greatest enemy of sound engineers, i.e. noise. To achieve this, new technologies were used and existing ones were adapted. ▌ About technology There are three main periods in the history of recording technology: acoustic, electric and digital. Each of them was revolutionary and changed music itself for good. As SUSAN SCHMIDT HORNING writes in Chasing Sound, changes in standards led to a change in sound and to new methods of production and distribution of recordings, which in turn shaped audience expectations and tastes, as well as musicians and composers to their work (p. 6). As an example, she cites the transition from acoustic to electric recording. In the former, the most famous were singers with a powerful voice, even if they were not particularly sublime. Correct recording of the signal through the tube required high sound pressure. When the microphone appeared in the studio, they receded into the background, and performers with softer voices, such as Peggy Lee, began to make their careers. So technology has influenced, and still affects, what we listen to, and how we listen. Technology, in a word, changes us. As long as we believed that we were its masters and that we were shaping it, there was nothing to wonder about. Today we are wiser with developed knowledge and we cannot pretend that technology is "transparent". It is already known that it develops independently of us. If something can be invented, it will be. If an invention can be used, it will be used. Moreover, an attempt to predict the effects of the introduction of a given technology is fundamentally doomed to failure. Among other things, because narrow specializations are promoted, but also because the effects of these changes are distant in time.

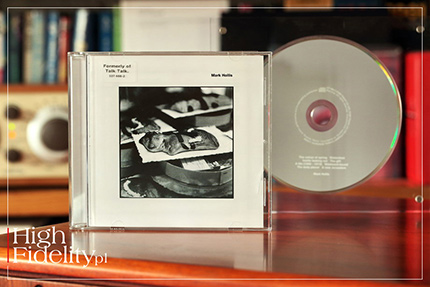

⸜ One of the best albums recorded using Mitsubishi tape recorders - debut of MARK HOLLIS (Talk Talk); is a hybrid recording, created using both an analog and a digital tape recorder. NATALIA HATALSKA in her work entitled Wiek paradoksów. Czy technologia nas ocali? evokes the example of hunters hunting mammoths in this context. Their goals were right - it was to feed the members of the tribes that took part in the hunt. However, their actions led to the extinction of these animals. The immediate effect was the need to change the diet, and thus the lifestyle. A far more long-term correction, however, was changing the entire ecosystem. According to Hatalska, after their elimination, completely new plant species and new predators appeared. Combined with the development of agriculture and medicine, this resulted in an increase in the population in the long term (p. 282). The cause therefore preceded the effect by thousands of years. Already in the 19th century, the Luddites, seeing the impact of new technologies on jobs, took up the fight against these changes. Although they were right on the merits, we remember them as "backward" people, and their name has become synonymous with backwardness and techno-phobia. It was not until 2004 that MAX MOORE, a transhumanist, defined the proactionary principle, and a year later the European Union adopted the precautionary principle. The latter says that if human activity could lead to any morally unacceptable damage, even if this damage is only hypothetical, action should be taken to avoid this damage (source: Hatalska, p. 301). The same is true of recording technology. Each change, although intended to lead to a more perfect sound, sacrificed something in the name of progress. It is no coincidence that we have such a big conflict in audio between the supporters of "analog" and "digital", between those who choose tubes and those who prefer transistors. And there are those who believe that the world of shellac is the last world in which the recorded sound sounded natural. At the same time, they forget about the existence of a large group of people who believe in the supremacy of Edison's vertically pressed cylinders; more regarding shellacs → HERE. This is the aftermath of the unregulated growth of technology. We don't see these tensions in this way on a daily basis, but if we want to be aware of our choices, we should know where they come from. And it's not, absolutely not, about being against technology. It's like being offended by our genotype. Because something in it does not suit us, something is wrong, something we would improve. It's just nature - as I mentioned, technology is now understood as something almost alive that has its goals and methods to achieve them. It's about consciously accepting change and choosing what's best for you. Hence my attempts to familiarize you with digital technology in audio. DAW stations are its last manifestation so far. Interestingly, although invented many years ago, they have no identifiable successor at the moment. Their development goes deep. New plug-ins are added to the basic sets, and the world of sound engineers is delighted with the possibilities offered by Dolby Atmos technology. The latest hit is automatic mixing and mastering, reaching for machine learning (so-called "artificial intelligence"). I don't see any signs that research is underway to improve sound quality. Thus, the story that began in January 1971 with the first Denon disc blew up and found itself in limbo. ▌ Progres, or regres? THE FIRST DIGITAL TAPE RECORDERS, both of the first generation, i.e. Denon and Soundstream, and the later Decca system, were based on tape transports originally intended for recording analog video (Denon and Decca) or for recording measurement signals (Soundstream). The digital signal, "pretending" to be analog, was recorded obliquely by the rotating head on a wide tape, moving at high speed. In order to record such a signal and then play it back, special devices were needed, which were a kind of "add-on" for the aforementioned transports. Thanks to the exceptional mechanical construction and attention to detail, the sound obtained from these devices is still astounding to this day. |

⸜ ADAM CZERWIŃSKI with Pictures in January 2021; it was recorded in analog domain, but later it was transferred to eight tracks on an ADAT tape recorder • photo Adam Czerwiński It surprises above all with its perfect tonal balance and great dynamics. The resolution of small signals was not the best, the D/A converters were quite primitive, and yet the definition of sounds is better than in most modern recordings. The first recordings in both systems were often made as "backups" for direct-to-disc sessions, i.e. the pinnacle of analog recordings, and many times producers, engineers and musicians pointed to digital versions as the better one. The next generation of recorders with fixed heads, i.e. Mitsubishi ProDigi, Sony DASH and M3, was much smaller, easier to use, and the tape transports used in them were modifications of the mechanics previously used in analog tape recorders. Scaling the tape recorders allowed them to be used in various places, transported and rented. And most of all, opened a multi-track world to digital recording, i.e. the world of pop and rock - for Mitsubishi and M3 it was 32 tracks, and for Sony first 24 and then 48. Because although the Soundstream system offered four channels, and the later Denon tape recorders even eight, it was far too little for producers of recordings of this type of music - 24-track recording was the standard at that time. The sound they managed to get this way was really very good. However, in direct comparison with the recordings of the first generation, attention is drawn to the lower dynamics and poorer definition of sounds. I am generalizing, a lot depends on a specific case, but it is a generalization supported by many listening sessions. Compared to contemporary recordings, it still sounded great. The problem with these three formats turned out to be something that I would call the "cautiousness" of the sound engineers. Digital technology was something so radically new that audio people had to rebuild their "workflow" to adapt to different requirements. This is why most recordings from this period have a weak bass base and sound a bit anemic. I think that the mastering systems in record labels and the fear of signal distortion are to blame for this. And only hybrid techniques, i.e. digital recordings, but combined with mixing and mastering on analog tape, made it possible to use everything that digital technology offers and avoid its problems. This was the case with PATRICIA BARBER’S Cafe Blue (Mitsubishi) and DIRE STRAITS’ Brothers in Arms (Sony); the debut of MARK HOLLIS (again Mitsubishi) was an example of the opposite strategy - the analog recording was recorded on a digital tape recorder and mixed in analog. All the recorders we talked about were big, heavy and damn expensive - both to buy and to maintain. Therefore the introduction of ADAT tape recorders in 1991 changed the rules of the game. These nominally eight-track machines, which could be combined into systems of up to 128 tracks, used inexpensive S-VHS video cassettes. Technically, it was a regress from the reel systems of the previous period. Transports and videotapes were used again, only now much more primitive ones. However, the abrupt reduction in the costs of acquiring and using recorders gave an impulse to the creation of a lot of independent, small studios, often simply "home studios". As a result of this change, many independent producers and sound engineers popped up on the market, operating outside the network of large studios, previously the "absolute" rulers of the professional industry.

Despite the primitive way of recording, the ADAT tape recorders produced a whole range of fantastic recordings, both in terms of sound - to recall PATRICIA BARBER’s Companion and JOHNY CASH’s My Mother's Hymn Book, as well as the music; examples include ADAM CZERWIŃSKI’s Pictures and ALANIS MORISSETTE’s Jagged Little Pill. In all these cases, the small size of the devices and low costs allowed manufacturers to be more creative, resulting from creative freedom. Interestingly, the best sound in these cases was again obtained by mixing the material in analog to an analog "master" tape. The inflation of the costs that had to be incurred to prepare a professional recording also brought about an inflation of sound quality. It broke the monopoly of "majors", as they are called today, but also - in the long term - led to the collapse of large studios that could afford top equipment and financed research on it. This, in turn, led to a sharp deterioration in the quality of the recordings. As the producers and sound engineers point out, a side effect, but a harmful one, was the disappearance of places where new producers could train under the supervision of experienced people. This led to the impoverishment of knowledge about recording technology and the disappearance of many skills. Of course, we are talking about a general rule, because there are obviously exceptions to this. Classic Albums magazine in an article titled How Has The Recording Studio Affected The Ways In Which Music Is Created? quotes Paul Théberge as saying:

The next stage, which mentally turned out to be an even deeper return to the past, were RADAR hard disk recorders, presented already in 1993. It was the first non-linear sound recording system in history. The operator had a computer keyboard and monitor at his disposal, which appealed to those who believed that the future of recording lay in computers. And yet it was treated by the operators like an improved analog tape recorder. They pointed to a similar sound with the addition of direct and instant access to selected places in the recording. The problem was the limited editing capabilities. Apart from making work easier, this system did not affect the work of recording studios or music. What began with the advent of ADAT tape recorders was completed by DAW systems, i.e. computer audio stations. We are talking about the democratization of the means of recording and the lowering of the standards for the recordings themselves. Computer systems gave recording industry tools with which they could counter their lack of skill and experience. Plug-ins like Auto-Tune have made it possible to create perfect "products" in a studio that fits - literally - in a laptop.

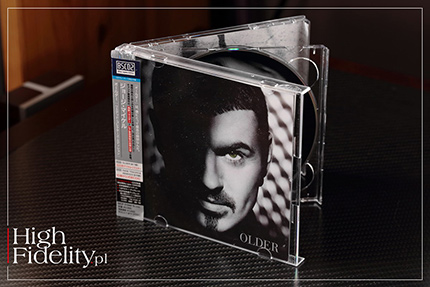

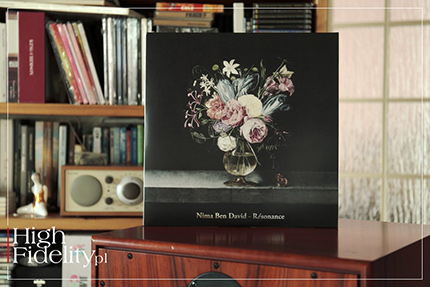

⸜ One of the best recordings - NIMA BEN DAVID’s Résonance by M•A Recording. The material for it was recorded directly on two DSD 5.6 MHz tracks. Once again, technology has been used to minimize the negative effects of technology itself. What began in the 1960s as an attempt to reduce noise and distortion has taken the recording industry to a place where audio quality is, on average, very low. Yes, the recordings no longer hum. But also majority of them does not sound like the best analog or digital recordings - even from the times of tape recorders. ▌ What comes next? EXPERIENCE SHOWS that there is no turning back to full analog systems. There are, admittedly, few albums made in this technology, but it is - from the point of view of the industry - an aberration and an absolute niche. Mainstream is digital and Protools. It turns out that the more technology in the recording and the less skills, the more refined "product" we get and the less important it is and the less important it is. From the point of view of those who profit from all this, this is an ideal situation. Digital music combined with streaming, which currently "serves" the absolute majority of the needs of music listeners and fans, constitute a dream ecosystem. The needs of fans are created, fueled and controlled in it. And all this with relatively small investments. The corporations also have absolute knowledge of our choices, and with the help of "learning" algorithms - another technology that was supposed to give us happiness - they can "tell us" what we like and what we don't like. And it can be done right. In each of the aforementioned articles, I showed recordings of exceptional sonic and musical beauty. The technology itself is just a tool. This is why even the simplest 16/44.1 digital recordings on two tracks and VHS tape, popular in Japan in the early 80s, are insanely good. The best recordings in DAW are also outstanding, especially if they were made in DSD, and if in PCM then by the best sound engineers. For this to work, however, a given project requires commitment, knowledge and talent. In all cases, three things drew attention: the proficiency of the producers, the minimization of the recording path and something that binds it all together, and what I would call LOVE. I'm not talking about the hippie or new age meaning of the word, but about something true and real. It would be a in-depth involvement on an emotional level of the people responsible for the recordings. Because what the Beatles sang is true: "All You Need Is Love". Then even technology can be useful, and we can get top sound with it. ● |

UBLISHING AT THE BEGINNING OF 2017 the article Digit in the world of vinyl. Trojan horse or necessity?, in which I described the first two technologies of digital sound recording, it never even crossed my mind that it would take me five years to study this subject and that I would write almost two hundred pages trying to describe this phenomenon and explain its consequences.

UBLISHING AT THE BEGINNING OF 2017 the article Digit in the world of vinyl. Trojan horse or necessity?, in which I described the first two technologies of digital sound recording, it never even crossed my mind that it would take me five years to study this subject and that I would write almost two hundred pages trying to describe this phenomenon and explain its consequences. The home studio has become a site of significant musical activity at every level, from professional to amateur music making, and a focal point of the consumer market for suppliers of electronic musical instruments.

The home studio has become a site of significant musical activity at every level, from professional to amateur music making, and a focal point of the consumer market for suppliers of electronic musical instruments.