|

TECHNOLOGY MITSUBISHI ProDigi

It is the story of the birth of digital audio, as well as a journey through the 1970s and 1980s, the best period in the history of digital recorders, and, finally, the story of their unique representatives – digital reel-to-reel tape recorders from MITSUBISHI. |

|

Technique

Text: WOJCIECH PACUŁA |

|

No 200 January 1, 2021 |

| A FEW WORDS ON DOGMAS Digital recording is especially close to my heart. As far as doctrines which constitute the basis of the audio industry are concerned, i.e. when it comes to the ANALOG → DIGITAL dispute, I am an agnostic. I know a lot of excellent analog recordings… and even more really bad ones. It is similar in the case of digital recordings. However, I think that music itself and its production are much more important than the domain in which the given recording is made.

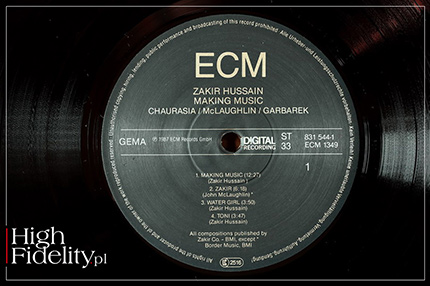

From 1986 (since August) to 1990, most ECM recordings were made using Mitsubishi X-850 tape recorders, hence the words “Digital Recording” on their labels. However, it does not mean that we obtain the same results in both cases. It is actually exactly the opposite: analog recordings almost always sound a little different from digital ones (and vice versa). In most cases, at least in my opinion, it is not a zero-one difference, but a difference in taste. However, when talking about the “analog” and “digital”, I have to mention that, statistically, I have more good analog recordings than digital ones in my collection. And I really do not know whether it is the result of subconscious choices, or a thing that depends on the music that I listen to. Anyway, I am not dogmatic. I have no data to unequivocally state that “this” is bad and “that” is good. As for the changes in the methods of recording and reproducing sound, I see what there really is in them, i.e. the tendency among musicians and producers to make as creative use of the recording studio as possible (the case of “the studio as a musical instrument”), to bring down the cost of recording (the “egalitarian” function), to make money (the basic function), as well as attempts to improve sound (the “qualitative” function). Bringing everything down to sound only is a misunderstanding and a sign of extreme ignorance. This is also the way I see the change in paradigm and the shift from analog to digital recording. In order to save your time, however, I will focus on technology. It must be clarified why such giants as Nippon Columbia, Mitsubishi, or Sony “entered” the digital domain so powerfully at all. In all these cases, the the key driver was the desire to eliminate the flaws of analog recordings. The apologists for the medium almost always forget that it is a faulty format and that at the peak of its popularity, i.e. in the 1960s and 70s, it was literally hated by many sound engineers. New technologies were to bring about, in the first place, a reduction in noise – and that was successfully accomplished. They were also to limit signal degradation during subsequent track recording and, finally, during mastering, which was also successful. Moreover, it was important to reduce harmonic distortion and eliminate sound swaying – also “done”. However, not everything turned out the way it was expected.

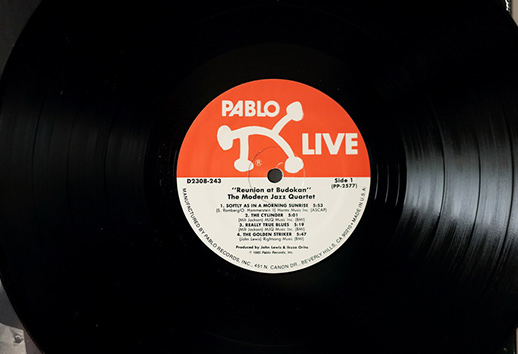

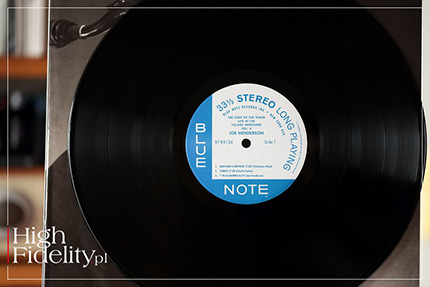

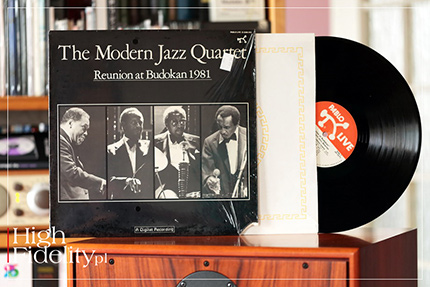

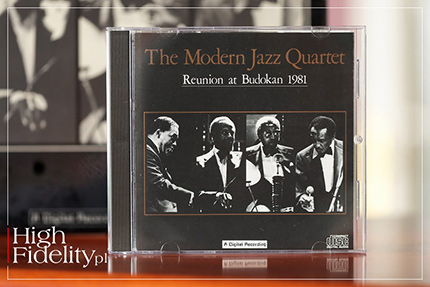

The Modern Jazz Quartet album released in 1981, recorded using digital tape recorders – hence the proud inscription “A Digital Recording” on the cover. Nobody expected that entering the digital world would revolutionize the way the audio market works and lead us to the lo-fi world we live in, dominated by the economical aspect of recordings, i.e. the tendency to reduce their cost, in combination with the populist and opportunistic approach to the role of the listener in shaping sound, i.e. the consent to total compression or a silent assumption that listeners “won’t hear anything anyway” and, finally, record making aimed at listening in a car, and using poor quality headphones. All of it led to a sound catastrophe. Despite noble intentions that guided the engineers who built the first digital recorders, their invention was degraded. And the degradation was part of this format from the very beginning. | FOUR ALBUMS, FOUR TYPES OF RECORDINGS Everything that I am talking about pertains to the mass market, of course. Fortunately, there are still record labels that take care of sound, as the ECM is still releasing ingenious digitally recorded CDs and we also get DSD-encoded recordings that sound wonderful. However, they are based on the experience that we talked about in the previous parts of the article and that we will elaborate on here. Let me recall the previous parts: • TECHNOLOGY: MITSUBISHI ProDigi, i.e. on digital reel-to-reel tape recorders once again | part 1 | read HERE • TECHNOLOGY: MITSUBISHI ProDigi, i.e. on digital reel-to-reel tape recorders once again | part 2 | read HERE In order to complete this cycle, I have looked at four more albums for you, prepared using at least one Mitsubishi tape recorder. Each of the recordings is different, as they were engineered in various ways: |1| Type: a digital two-track “live” recording, direct analog mix onto the X-80 I have used different media – both original LPs and their reissues, CDs and SACDs. The LPs were played on the TechDAS Air Force III turntable with the SAT LM-09 arm and the Miyajima Laboratory Madake or X-quisite ST cartridge, while the CDs and SACDs – on the Ayon Audio CD-35 HF Edition SACD player. |1| JOE HENDERSON

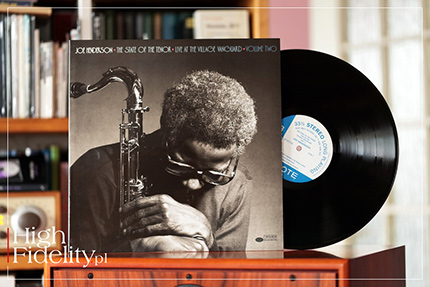

Musician | JOE HENDERSON (1937-2001) was an American tenor saxophonist, one of the most important artists of the Blue Note record label. Between 1963 and 1968, he recorded almost thirty albums for it, including five as a leader. He cooperated with, among others, Horace Silver, Herbie Hancock or Lee Morgan. As for music, these albums are stylistically quite diverse, as they include both classic hard-bop (Page One, 1963) and more future-oriented sessions from the albums Inner Urge and Mode for Joe (1966), as well as music close to free-jazz from the album that is being discussed here. In the 1980s, he mainly performed as a leader, both reinterpreting standards and playing his own compositions. In 1986, Blue Note decided to crown the artist’s presence in its catalogue by organizing a concert at the Village Vanguard club in New York and releasing the recording on an album, or actually two: State of the Tenor: Live at the Village Vanguard, Volume 1 and State of the Tenor: Live at The Village Vanguard, Volume 2. The saxophone-playing leader was accompanied by RON CARTER on the double bass and AL FOSTER on the percussion. Almost the same trio had been recorded for Blue Note in 1957 at the same club, but the difference was that Sonny Rollins had played the saxophone back then. Venue | | In the case of this album, we are talking about a single “concert”, but these were actually three days from which tracks for both albums were selected: the performances took place on November 14th, 15th and 16th, 1985. In this way, Henderson became part of the beautiful history of the Village Vanguard. The jazz club was opened in 1935 on Max Gordon’s initiative. Initially, it featured folk music and comic performances, but in 1957 it became a classic jazz venue.

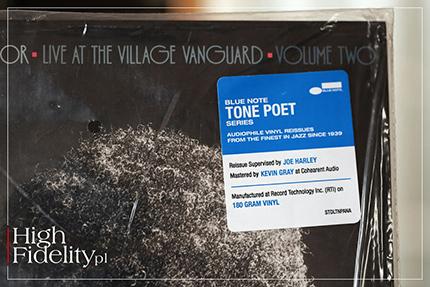

Henderson’s album released by Blue Note featured no information that it was a digital recording. The club owner chose to invite “classic” musicians to perform at the venue, such as Miles Davis, Horace Silver, Thelonious Monk, Gerry Mulligan, the Modern Jazz Quartet, Jimmy Giuffre, Sonny Rollins, Anita O’Day, Charlie Mingus, Stan Getz and Carmen McRae, while Bill Evans was also a regular visitor. Rollins’s performance mentioned above was a really important event. It constituted the first recording session at the venue, released on three LPs. Let me remind you that in part 2 of this article we had already described one of the concert albums recorded at the Village Vanguard – i.e. Steve Kuhn Trio and Life’s magic. In both cases, the person responsible for recording was DAVID BAKER. Recording | So, the performance by Henderson’s trio became part of the long tradition of the venue and, in a way, put the final dot in the story started by Sonny Rollins in 1957. However, in many respects, it was a completely different session. Even though it was recorded directly onto two tracks, with a mix using an analog console, analog tape recorders were replaced by digital ones. It was because two reel-to-reel Mitsubishi X-80 tape recorders had been installed at the club some time before. For a long time, nobody knew that the albums released at the time, cut using DMM technology, came from digital recordings (50.4 kHz and 16 bit). A “standard” version was only released in France. Let me add that the album was finally released in1987, i.e. two years after the recording had been made. Vol. 1 was released first and then more recordings were selected to complete vol. 2. Unusually, one cannot say that vol. 1 is better than vol. 2 – the selection was an arbitrary decision of the record producer. It even seems today that Vol. 2 is more interesting than Vol. 1. Re-issue | | Perhaps this is due to the recording method used – the albums have not been re-issued on LPs before, but only on CDs, after the conversion of 50.4 kHz signal to 44.1 kHz. The first digital edition from the year 1987 features the SPARS DDD code that informs us about the recording method, which disappeared in the subsequent years, as if the record label was ashamed of it. As for the LP edition, there is no information concerning the recording method. This may be the reason why most online stores, even Acoustic Sounds, while describing the latest re-issue of the album that has been released as part of the “TONE POET” series, talk about a remaster from “analog tapes”. You may be mistaken by the fact that this is a series in which discs are actually cut from analog “master” tapes. When asked about it during an interview for the online magazine arkivjazz.com, the producer of the series, Joe Harley, said:

So, the album State Of The Tenor: Live At The Village Vanguard, Volume 2 was recorded onto two digital tracks, while the material was either cut and edited, or simply recorded digitally onto another digital tape recorder together with edition. This would normally entail sound degradation – lower, however, in the case of a digital copy. Kevin Gray was responsible for mastering. Unfortunately, it is not known if the remaster was made directly while lacquer was being cut onto an LP from a Mitsubishi tape recorder, or signal was recorded into files and thus mastered. The former method would have been much more transparent, as it would not have been necessary to convert the untypical sampling frequency of X-80 tape recorders.

Even the label on the latest reissue of the album as part of the “Tone Poet” series does not inform us that this is a digital recording. We can learn something about it while comparing it to the labels of the remaining albums, which say: “Mastered From Original Analog Tapes”. Sound | This is an album that sounds absolutely fantastic on vinyl. It is characterized by incredible dynamics and exceptionally clear – this may be something that the people who designed digital tape recorders dreamt about and usually did not get. Clarity is a natural element of the musical message here and it does not dominate. And the strike! The percussion sounds ingeniously fast, which is rare. It is neither covered by a “veil”, nor soft. Tonal balance is slightly shifted towards the upper midrange. However, the change is small and probably results from the fact that we cannot hear the “tuning” of the lower midrange that is typical for vinyl. Johnson’s album sounds more like a “master” tape rather than its copy – be it an LP, or a CD. It is “instant” and punctual sound. Music from the album The State of The Tenor is rhythmically complex, which is hard to handle by the reading system, independently of the medium. In this case, in the “Tone Poet” reissue, we get the best version of the music. Let me add that bass is deep and dynamic. It is hard to call it “saturated”, as it is not as soft as in jazz recordings made using classical analog technology. Here it is closer to what I know from the stage, from a concert. It is a bit hard, just like the entire musical message, but this appears to be part of the entire package that we get with recordings made using a digital Mitsubishi tape recorder. It is one of the best-sounding modern jazz albums, characterized by incredibly clear and dynamic sound that wonderfully depicts “live” events – and this is what a concert should sound like, isn’t it? |2| MODERN JAZZ QUARTET

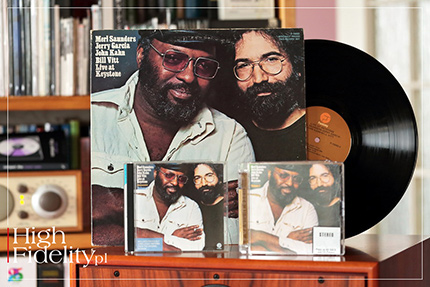

THE MODERN JAZZ QUARTET is one of the most well-known and respected jazz bands in history. It has included instrumentalists known from solo projects, as well as countless sessions of other most popular artists. Even though its members have changed with time, it mostly included John Lewis (piano), Milt Jackson (vibraphone), Percy Heath (double bass) and Connie Kay (percussion). There is still disagreement over whether the leading instrument was Lewis’s piano, or rather Jackson’s vibraphone. The band grew out of a section accompanying Dizzy Gillespi’s big band, which he performed with from 1946 to 1948. In 1951, they were known as Milt Jackson’s quartet which turned into the Modern Jazz Quartet in early 1950s. Lewis became the music director for the band, after which they made a few recordings for Prestige Records. In 1956, the band moved to Atlantic Records and had its first concert tour around Europe. The 1970s brought an end to the band’s most intense period of activity, when Jackson left in 1974. He was frustrated and tired of constant concert tours, and he only decided to return in 1981. The last recordings were made in 1992 and 1993. After Connie Kay’s death in 1994, the band remained semi-active and ultimately stopped performing in 1997. |

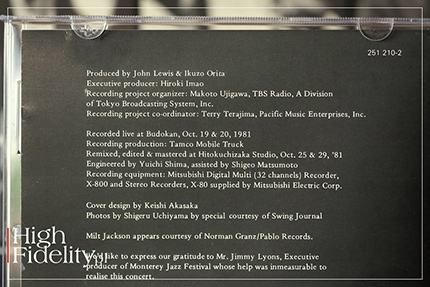

Recording | The concert Reunion At Budokan 1981 took place at the beginning of the band’s “reactivation” in the early 1980s, on October 19th and 20th 1981 at Nippon Budōkan (Japanese: 日本武道館), Budokan for short. It is one of the most important indoor arenas in Tokyo, built in 1964. It was designed by Mamoru Yamada who was also responsible for the Kyoto Tower, as well as a lot of buildings that were developed on the occasion of the Olympics in Japan (1964). The concert was part of the Pioneer Live Special series of performances. It is a beautiful combination of seemingly distant elements which rarely go together so nicely, i.e. the recording was made using the digital 32-track Mitsubishi X-800 tape recorder, which constituted an absolute novelty at the time, and mixed in the analog domain onto the two-track digital X-80 tape recorder from the same manufacturer. Engineers working for the NHK, the Japanese national broadcasting consortium, were pioneers of digital recording on reel-to-reel tape. Their work was based on was done during TV broadcasts at the time of the abovementioned Olympics in1964. So, sound was recorded by devices that are directly connected with the venue where the concert of the Modern Jazz Quartet was organized.

The CD version was released by the Warner-Pioneer Corporation in Japan, but the disc was made in Germany. The Pablo Live issue cover differs from the original with its white letters and a white rim instead of a gold one. Sound was recorded at the Tamco Mobile Truck studio and mixed at the Hitokuchizaka Studio, under the supervision of Yuichi Shima, only a few days later (on October 25th and 29th). Using a multi-track digital tape recorder was equal to dealing with state-of-the-art digital technology of the time. Stereophonic signal also had a digital form, 16 bit resolution and 50.4 kHz sampling frequency. This particular tape was used to cut lacquer for the LP edition that was also issued that year. Issue | The album Reunion At Budokan 1981 was originally released on an LP by Atlantic Records – in the USA and Japan at the same time. It is interesting that it was also issued in Brazil and Argentina. The digital version was produced later, in 1984, when it was released in Japan and Germany by WEA (Warner Elektra Atlantic). It is important that the Japanese version was pressed at the same pressing plant as the German one, i.e. the German Record Service GmbH. In order for it to work out, signal had to be converted to 44.1 kHz. A reissue on an LP was released in the USA (Pablo Live) and Japan (Atlantic) a year later. There are no later reissues of this album on any medium. I used a European reissue (1985) and a Japanese CD version of the album (1984) for comparison. Unfortunately, the original LP version did not arrive in time from Japan.

The CD version features carefully compiled details of the equipment used for recording, as well as a list of people responsible for this issue. Sound | The concert of the “reactivated” Modern Jazz Quartet was recorded right after the “birth” of the DigiPro format, i.e. at a time when sound engineers and record producers were still not ready for what it offers. However, the version being discussed is perfect. Its sounds a little light, which is a common feature of all the recordings in which material was mastered using the X-80, but not too light. Simply speaking, high sound energy is located within the midrange and treble, as both Lewis plays his piano mainly in upper registers and Jackson’s vibraphone has naturally high sound. The clarity of the instruments, as well as of the strong percussion, is beyond any dispute, as digital recordings made later rarely even attempt to accomplish anything similar. There is no saturation known from the analog recordings of the 1950s here, it is just not that type of aesthetics. Emphasis is put on the treble and the album is live and dynamic, which is something that digital Mitsubishi tape recorders specialize in. The resolution of the cymbals and vibraphone sound is fantastic, even though we are talking about a 16-bit remaster here. DodamLet me also add that the CD version is much less open and more muffled. It is still a very good recording, but does not have the energy and open character of the LP issue. |3| MERL SAUNDERS, JERRY GARCIA, JOHN KAHN, BILL VITT

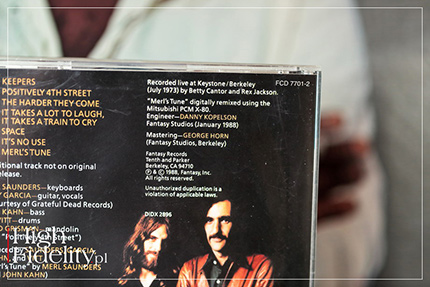

Musicians | Live At Keystone is a concert album recorded at a small club called Keystone, aka Keystone Berkeley, located at University Avenue 2119, Berkeley, California. This is the place where the Grateful Dead band performed, which became a kind of home for its guitarist and vocalist, JERRY GARCIA, who later performed there with his Jerry Garcia Band set up in 1975. Garcia also performed there with MEL SAUNDERS, the master of the Hammond B-3 organ, whenever he was not on tour with the Grateful Dead. They are accompanied by John Kahn on the double bass and Bille Vitt on the percussion and keyboard on the album. Recording | The performance was recorded on July 10th and 11th 1973 on analog multi-track tape, to be released a year later as a double LP album. In 1988, the Fantasy Records record label remixed the material, adding tracks that had not been published before, and reissued the album on two separate CDs, entitling them Live at Keystone Volume I and Live at Keystone Volume II. It is interesting that the first edition of the new, remixed version of the material features the information: “Merl’s Tune digitally remixed using Mitsubishi PCM X-80”, suggesting that only one extra track was remixed. However, it seems that the whole album was remixed at the time, which is proven by the ℗&© logotypes (1988) – this means we are dealing with new material.

The 1988 CD issue bears the information that only one track was digitally remixed, but its copyright labels suggest something else. So, we are dealing with a case when an album is recorded, mixed and mastered in the analog domain, but its reissue is mixed and mastered digitally, onto the X-80 tape recorder. So, the CD was made using a “master” tape (16 bit and 50.4 kHz) and it means some kind of a converter must have been used to change the sampling frequency to 44.1 kHz, and such actions are never “transparent”. I do not know how it was with the SACD released by Fantasy Records in 2004. The cover features the same information as the CD, so we could assume it is the same material, but it could have as well been taken directly from the analog X-80 output and only then converted into DSD. This is what Tom Jung did with his DMP record label album reissues – he thought the method was better than digital conversion. For comparison, I had the original analog version of the album (1973), as well as its CD reissue (1988) and a SACD (2004). Sound | The original issue of the album Live At Keystone sounds quite soft and dark. It is the pleasant sound of the 1970s, without clear textures or a clear attack. Not that I am complaining, as it is a very pleasant recording and great music, but there is not much to talk about. The digital CD reissue of the album (1988) is not the best. It somehow loses the softness and charm of the original, while offering brighter and harder sound. The brightness is not accompanied by more details, however. It may seem so, but only if we have not listened to the original analog edition before.

That is why the Super Audio CD version (2004) is so surprising. It is simply incredible, as it combines the softness of the original with the openness of the CD version, in a mix which gives us the best of both worlds. Signal is more compressed here than on the LP, but it seems that the material was prepared using the digital remaster from the year 1988. Because of that, more emphasis is put on attack here than on the LP, which is the only disadvantage. However, the whole thing sounds coherent, nice and colorful. Thus, it is one of the best digital reissues of the album made using the X-80 tape recorder. |3| GARY PEACOCK

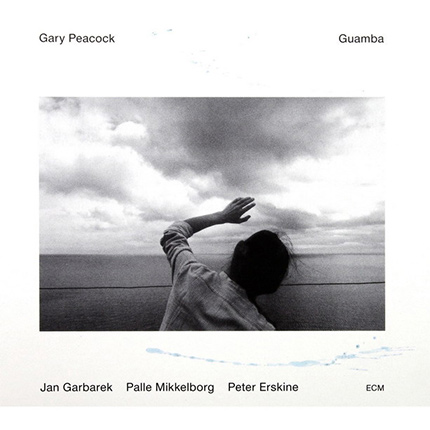

The test press version of the Guamba album! Guamba is GARY PEACOCK’S own album. The American double bass player is accompanied by Jan Garbarek on the saxophone, Palle Mikkelborg on the trumpet and Peter Erskine on the percussion. Almost all of the tracks included were composed by the leader and the recording took place in March 1987 at the Kongshaug studio – Rainbow Studios in Oslo. Its basis at the time was an analog Soundcraft mixer and signal was recorded onto one of two available 32-track digital Mitsubishi X-850 tape recorders (16 bit, 48 or 44.1 kHz). So, the recording was digital, mix – analog, while master – well, I don’t really know. There were both the digital Mitsubishi X-86, as well as two mastering analog tape recorders at the studio. Let me add that the Mitsubishi tape recorders were placed there in August 1986. LP records produced in this way by the ECM record label featured the words: “Digital Recording” on their stickers. I had the “test press” version of the album for the listening session.

Sound | I have decided to discuss this album at the end, as the person responsible for making it, Jan Erik Kongshaug, the major sound engineer for the ECM record label, found the golden means to deal with sound, using both digital and analog technology in a hybrid combination. Jan Erik Kongshaug’s recordings have almost always constituted real masterpieces. It can be disputed whether it would be better to show instruments further away or closer, or how much reverberation should be used, but we are talking about an extremely high standard here. It is the same in the case of digital recordings, including the ones he made using Mitsubishi tape recorders. So, Peacock’s album is saturated and dense. The opening double bass has proper weight, fill and color. The sound is spatial and open, which is typical for ECM recordings. It seems to me that the sound is slightly clearer than in analog recordings and the attack of the instruments, mostly of the percussion, is outlined a little more clearly. The sound is neither as saturated as in the earlier recordings, nor as warm as on the contemporary albums published by the record label (DDD). One can also hear Mitsubishi’s signature in the very open midrange, exceptionally clear cymbals and extremely well-presented strike on the timpani and snare drums. It is an incredible recording! What I missed a little bit was a slightly more varied sound texture, especially when it comes to Grabarek’s saxophone. Apart from that, however, it is an example of what digital recordings might sound like if only the advantages of Mitsubishi tape recorders were utilized without being influenced by the drawbacks. | AN ATTEMPT TO SUMMARIZE EVERYTHING How to sum up millions of dollars, hundreds of thousands of hours and the talent of tens of engineers in one short sentence? It is simply impossible. Mitsubishi ProDigi tape recorders were inspired by an engineer-audiophile and they constituted state-of-the-art digital technology at their time. Alongside Sony DASH tape recorders, they set up a standard that was never improved afterwards. These were the last so technologically advanced digital recorders in the history of audio. However, that does not mean that the recordings which were made using these recorders are flawless. Paradoxically, from among the hundreds of albums and recordings that were created with the help of tape recorders featuring the letter “X” in their symbol, a lot are of doubtful sonic quality today. Where does the problem lie? Well, they are usually tonally too light, as too much attention has been paid to the treble and because of the fear to complete everything with meaty bass. I believe that this is mainly the problem of sound engineers and people responsible for cutting lacquer, as Hollins’s, or Henderson’s records prove it can be done perfectly. The digital recordings discussed here differ from the earlier analog ones in terms of much better treble. Never before and rarely afterwards was the treble characterized by such incredible dynamics and precision. The problem with the recordings was that they were characterized by an incompletely filled “body” and a lack of warmth in the midrange. The earlier warmth was an artifact added by vinyl and tape, but it is something we have got used to. It is interesting that digital recordings sound closer to what we know from a “live” recording here – no wonder, as a lot of albums developed using ProDigi recorders were created during concerts.

The audio system used for the evaluation of the recordings However, the biggest flaw of recordings made mainly with the use of the Mitsubishi recorders is a lack of something that one might call completeness. Its shadow appears in the best recordings, but it is never fully accomplished. The major advantages of the devices are perfect dynamics and a precise, fantastic signal attack. So, perhaps the sound engineers and producers who recorded material digitally, but mixed and mastered it in the analog domain were right (let me recall Patricia Barber’s album). I am really interested in what it would be like if the technology had developed for ten more years and had not been suddenly abandoned. That might have prevented DAT, i.e. Digital Audio Tape, from becoming the most popular mastering medium in the 1990s. It was a budget version of digital tapes from the 1980s, constituting one of the most unreliable and least credible media of this type. However, this is how the world works – technology develops and then diminishes, according to the demands of the “mainstream”. And it is the latter tendency that has greater impact on us. ■ | SOURCES

|

n the first two parts of the article on digital reel-to-reel tape recorders from Mitsubishi, we first looked at the first digital recorders that were introduced at the beginning of the 1970s and reigned until the end of the 1980s (and often even longer – PART 1

n the first two parts of the article on digital reel-to-reel tape recorders from Mitsubishi, we first looked at the first digital recorders that were introduced at the beginning of the 1970s and reigned until the end of the 1980s (and often even longer – PART 1