No. 261 February 2026

- COVER REVIEW: TECHDAS Air Force IV ⸜ turntable » JAPAN

- RECORDING TECHNIQUE ⸜ music: 3M DIGITAL AUDIO MASTERING SYSTEM Part 2 || MUSIC » USA

- MUSIC ⸜ review: ARNE DOMNÉRUS, , Jazz At The Pawnshop, Proprius/AudioNautes Recordings MQA-CD Crystal Disc ⸜ 1977/2025 » SWEDEN / ITALY

- REVIEW: CIRCLE LABS AS100 ⸜ integrated amplifier » POLAND

- REVIEW: SHANLING EC Zero T ⸜ MQA-CD player • mobile » CHINA

- REVIEW: FEZZ AUDIO Sagita Prestige Evo & Olympia Evo Mono ⸜ linestage & power amplifier • monaural » POLAND

- MICRO REVIEW: ACOUSTIC REVIVE PS-DBLP ⸜ record clamp / stabilizer » JAPAN

|

Editorial Text: Wojciech Pacuła |

|

No 195 August 1, 2020 |

|

BLACK HOLE

Capelli Cracoviensis Choir capellacracoviensis.pl | photo: press materials

We live in a world of a lo-fi sound. All the solutions that were created after - say - the 1950s and 1960s were not aimed at improving the sound quality, but at better access, lowering the cost of recording and playback of music, and finally changing the paradigm of data storage and distribution. I am talking about data because with the introduction of digital recording to audio - and this happened in January 1971, when the first LP was released, for which the signal was digitally recorded - the recorded sound is no longer a continuum of information, but a data stream. Today, listening to the music from a smartphone using low-quality headphones is a new standard. Even those who choose higher quality headphones rely on smartphones as a source of sound and data streaming. And these data have been subjected to destructive treatments for many years. First, we dealt with hard to believe, even unbelievable compression (it is about the compression of an audio signal, not files), and this time, from, say, 2000 - is called the Loudness War. The next step was the transition from discrete systems in the recording studios to digital DAW (Digital Audio Workstation) platforms, with the most popular one called Pro Tools, until the entire process of creating the album, i.e. recording, mixing and mastering, takes place in this the computer itself; this process is called "in the box".

Screenshot of a typical DAW editing, photo Clusternote/Wikipedia This, of course, is nothing new, because the sacrifice of quality for the sake of "quantity" has been known in audio for years. Lets just recall the transition from 16-track recording on a 2” analog tape to 24-track recording on the same tape. In an instant, the frequency response dropped dramatically, but the distortion and noise increased. An equally destructive change was the widespread use of SSL and Neve mixing tables based on integrated circuits. Today they are considered classics, but when they began to be used, sound engineers collectively pointed to their poor sound. However, they had an important advantage: they allowed for automatic recall of settings, which facilitated the mixing of the material. So they were a part of the overall process of improving the recording process, not part of the perfectionist trend. The matter was completed by the digital revolution, including lossy MP3 and AAC compression that pushed the sound into an even smaller box (this time it's about data compression, so throwing out some information). Audiophiles have known all about these changes "for ever" and although their voice is ignored, often even ridiculed, thanks to them, in perfectionist audio we still deal with changes, often for the better. However, there is an area where it is not even about quality, but about the very existence of music. It looks like we live in a world that there will be very little left of after a while. The vast majority of music, film, many other artistic works, as well as simply human activity (such as communication) exist only in the binary world, i.e. in digital form. It allows easy manipulation, cheap transmission and distribution, as well as reading on any device. However, it so happens that it involves the least durable way of saving data as we know it. I think that it is no coincidence that in the two dystopias published in a short period of time, the time of digital omnipresence is referred to as a lost time for historians. Let me quote:

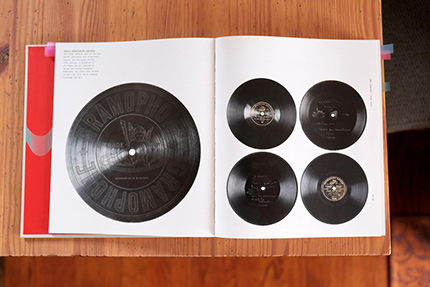

This is a fragment of Margaret Atwood's latest novel Wills. Robert Harris speaks in a similar manner about "data clouds" in his latest novel entitled The Second Sleep. Here the problem is much deeper, because it is not just about information gaps, but about the complete loss of all data and the return of humanity to the state of the medieval period. And one could shrug it off - it's just literature after all - were it not for the fact that artists are a bit like a membrane, much more sensitive to the world than the average observer, and thus catching things that elude others. Since this issue has been raised by scientists and engineers for years it makes it a fact, and yet it has been pushed to the fringe of everyone’s interests. The point is that digital media is the least durable way to store data. Never in the history of mankind has there been such a physics disregarding way of collecting information. There are two levels of this problem. One is related to the carrier as such. It is the fastest-changing element in the digital world. When Mitsubishi promoted its system as being the most reliable and "secure" in the early 1980s, it was hard to predict that eight years later these monstrously expensive devices would cease to be produced and their owners would be left alone with thousands of tapes no one knew what to do with. And yet an analog tape recorded in the 1950s is still easy to play and there are plenty of devices that can perform the task. On the other hand, when looking at computer technology, one could recall 3,5 and 5” floppy disks, which are today useless as we don’t have devices that could read them anymore, not to mention perforated tapes and less common computer media. And again - a gramophone record pressed in the 19th century can be successfully played today, while a floppy disk from ten years ago not so much. And this process will only get worse.

Early records – 10”, 78 rpm | source: Terry Burrows, The Art of Sound. A Visual History for Audiophiles, Thames & Hudson, London 2017 |

The second level is related to the very essence of digital recording. I don't know if you are aware of this, but every few years the data stored on the hard disk become so incomplete that it can be said that it is lost. That is why the archives are regularly performing complete data transfers to new disks. However if we forget one, and a few years later there will be nothing to save. Recorded discs, for example CD-Rs, have a slightly longer durability, but it depends on their quality. A cheap disc is often unusable after a year, a large part after a few years and only the best ones offer several dozen years of durability. But it is not known how many - it is still a too "young" format. Dr. Tomasz Łojewski, head of the Laboratory of Research on the Durability and Degradation of Paper at the Jagiellonian University, points out that on a CD-R we usually do not find information that it will only last, for example, 20 years,, because it would be alarming to a buyer who imagines that his great-great-grandchildren will be able to read the content of such discs. Well, he says, they won't be able to. At the same time, he introduces a distinction between 'medium' and 'information' - digital information as such is indestructible, because it can be copied endlessly, with imperceptible change of its content (in audio we know that it is not so, but in the world of data it is believed so) . Łojewski compares the change of a carrier of digital information to the replication of a genetic code. DNA is copied onto the new organism and therefore can be so long-lasting. Genetic information is not lost because it is copied onto new "carriers". That is why organisms on Earth have been functioning for many thousands of years. This is true. However, the carriers we use are extremely vulnerable to data corruption. Anyway, if this comparison was taken seriously, each copy of DNA introduces changes that change the organisms themselves. So what will remain after us? Probably some part of digital data, as long as they are properly and constantly copied onto new media. The vast majority of music will be lost, however, because it will be declared invalid or we will simply forget it. What is worth keeping and what is not will be decided by popularity, money and, to a small extent, professionals. We will be able to enjoy analog tapes for a long time. If stored properly, they will last for another fifty years. Steve Albini, a promoter of analogue productions, responsible for albums of such bands and performers as: Nirvana, Pixies, Mogwai, Robert Plant and Jimmy Page, and Manic Street Preachers says:

It may be a paradox, but the most durable musical medium known to us is a vinyl record. It is already known today that many titles exist only in this form, because varnishes, acetates, and then the master tapes were lost or damaged - see the history of the Impulse label archive! (more HERE). The very method of mechanical pressing of information into a quite durable material makes the LP record able to sound equally well after 50 years, and probably also after a hundred more years. Not played it will last as long as the material itself degrades.

solarsystem.nasa.gov accessed: 12.06.2020 This is why snippets of musical works that NASA sent into deep space with the Voyager probe in 1977 were recorded on a gold-plated copper plate; although the material of the disc is different, it is not vinyl or even shellac, the way of recording the signal is the same as on LPs (more HERE). Probably similar motives guided the Church of Scientology, which pressed the speeches of the founder L. Ron Hubbard on titanium plates (such as LP), locked them in metal, protective boxes and hidden in the northern part of New Mexico, 125 miles from Santa Fe, in a specially dedicated tunnel formed in the desert. A solar powered turntable is hidden along with the discs - its operation is explained with pictograms. The tunnel is closed with four doors, three of which are to withstand a direct nuclear attack, and without it - at least 1000 years. An interesting fact - also Compact Discs have quite a long lifespan, provided they are properly produced and stored. I think that a large part of them will last for several dozen years, maybe even more. Most of the titles from the early 1980s, when this standard came out, are in excellent condition. Also in their case, the direction is determined by the activities of the Scientologists aimed at preserving the words of the founder for "eternity". Hubbard's speeches, apart from LPs, were also stored on specially acidified paper and… Compact Discs made of pure gold applied to glass. So - they exist on Glass Discs, that we wrote about many times (e.g. HERE). Archivists believe that they have a service life of over 1000 years (more HERE). However, there is a medium that is much more durable - the already mentioned paper. It is one of the best information carriers known to mankind. According to the already mentioned Dr. Łojewski, an average book printed in Poland today will last a hundred or even 300 years. It is also known that high-quality, properly stored paper - possibly graphene in the future - has a shelf life of not hundreds, but thousands of years; you can read more about the archiving and durability of paper in a special issue of the journal "Archeion" (T. CVIII Warsaw 2005; pdf version HERE; access: 12/06/2020).

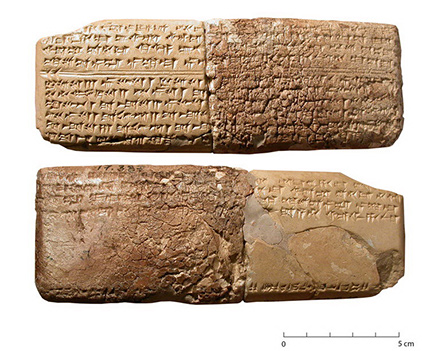

Ugarit tablet containing a record of the Hurrian songs, the oldest known musical piece. You can find it on a CD titled Music of the Ancient Sumerians, Egyptians & Greeks, perf. by Ensemble De Organographia (Gayle Stuwe Neuman i Philip Neuman), Pandourion PRDC 1005 (2006) | photo www.circlethroughnewyork.com So music has a chance to last a long time. In 1952, archaeologists working in the ruins of the ancient city of Ugarit, in what is now Syria, unearthed clay tablets with cuneiform writing, dated to 3,400 years ago. They contained symbols related to music - it is believed to be the oldest known musical notation. Perhaps it is so that what will be left of the music recorded mechanically will be first of all its written record, probably on paper. What about recordings? It may be the same with them. In 2008, David Giovannoni with his team at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California discovered the original recordings of a phonoautograph, the oldest device used to record sound. Patented in 1857 by the French inventor Eduardo-Léon Scott de Martinville, it recorded the vibrations of the membrane on a paper or glass, drawing a pattern on the soot. If we take into account the durability of paper and the impermanence of digital media, it is possible that the only recording our great-, great-grandchildren will hear will not be Chopin played by Pollini, not Lady Gaga, but a French folk song entitled Au clair de la lune, sung by the inventor of the phonoautograph. WP |

About Us |

We cooperate |

Patrons |

|

Our reviewers regularly contribute to “Enjoy the Music.com”, “Positive-Feedback.com”, “HiFiStatement.net” and “Hi-Fi Choice & Home Cinema. Edycja Polska” . "High Fidelity" is a monthly magazine dedicated to high quality sound. It has been published since May 1st, 2004. Up until October 2008, the magazine was called "High Fidelity OnLine", but since November 2008 it has been registered under the new title. "High Fidelity" is an online magazine, i.e. it is only published on the web. For the last few years it has been published both in Polish and in English. Thanks to our English section, the magazine has now a worldwide reach - statistics show that we have readers from almost every country in the world. Once a year, we prepare a printed edition of one of reviews published online. This unique, limited collector's edition is given to the visitors of the Audio Show in Warsaw, Poland, held in November of each year. For years, "High Fidelity" has been cooperating with other audio magazines, including “Enjoy the Music.com” and “Positive-Feedback.com” in the U.S. and “HiFiStatement.net” in Germany. Our reviews have also been published by “6moons.com”. You can contact any of our contributors by clicking his email address on our CONTACT page. |

|

|

e come home after a difficult day, or we just want not to do anything concrete, we fire up the computer, smartphone or something like that. We press "play" and ... there is silence, nothing happens. First, we think that we did something wrong, or incorrectly, then that maybe the device froze for whatever reason, and finally we start to blame the internet provider. However, this does not change the initial situation - we are not able to listen to the music which can be extremely frustrating. You think that it's unlikely, that it doesn't happen? Believe me, this is a "likely tomorrow" scenario, a part of a huge problem we have to face. This is a problem that can cost us all the music made in the last thirty - if not more - years.

e come home after a difficult day, or we just want not to do anything concrete, we fire up the computer, smartphone or something like that. We press "play" and ... there is silence, nothing happens. First, we think that we did something wrong, or incorrectly, then that maybe the device froze for whatever reason, and finally we start to blame the internet provider. However, this does not change the initial situation - we are not able to listen to the music which can be extremely frustrating. You think that it's unlikely, that it doesn't happen? Believe me, this is a "likely tomorrow" scenario, a part of a huge problem we have to face. This is a problem that can cost us all the music made in the last thirty - if not more - years.