No. 261 February 2026

- COVER REVIEW: TECHDAS Air Force IV ⸜ turntable » JAPAN

- RECORDING TECHNIQUE ⸜ music: 3M DIGITAL AUDIO MASTERING SYSTEM Part 2 || MUSIC » USA

- MUSIC ⸜ review: ARNE DOMNÉRUS, , Jazz At The Pawnshop, Proprius/AudioNautes Recordings MQA-CD Crystal Disc ⸜ 1977/2025 » SWEDEN / ITALY

- REVIEW: CIRCLE LABS AS100 ⸜ integrated amplifier » POLAND

- REVIEW: SHANLING EC Zero T ⸜ MQA-CD player • mobile » CHINA

- REVIEW: FEZZ AUDIO Sagita Prestige Evo & Olympia Evo Mono ⸜ linestage & power amplifier • monaural » POLAND

- MICRO REVIEW: ACOUSTIC REVIVE PS-DBLP ⸜ record clamp / stabilizer » JAPAN

|

|

|

PRAISE OF A (NON)FORMAT

It is exactly the same with the digital and analog music medium. The audiophiles words of wisdom usually start and end with analogue, and by the term "analogue" they almost always mean a vinyl record. Actually, both techniques have their advantages and disadvantages, as witnessed by people associated with the recording studios. Read a very nice interview with Tom Jung, the founder of the DMP company, who talks in a reasonable and consistent way about why he gave up the analogue himself and why he welcomed the digital era with open hands (see HERE).

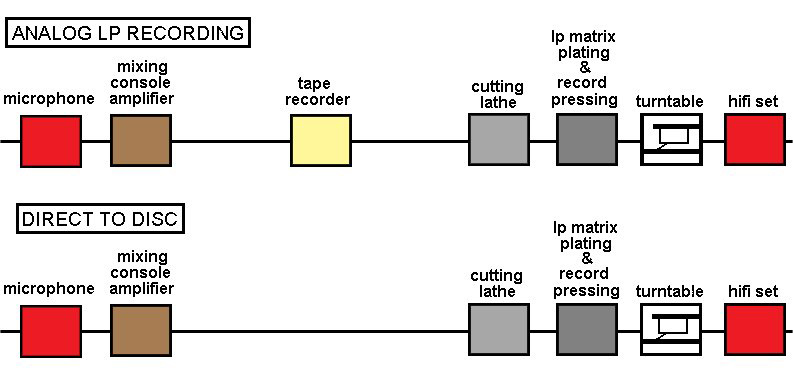

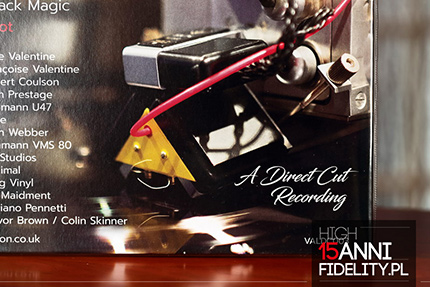

There are, of course, music lovers, sound engineers and audio journalists convinced that the analogue is the right and only way to listen to the music. Both of them are right. Yes, both. This is an interesting case of when the ironclad rule tertium non datur - one of the basic laws of the classical propositional calculus, saying that “There is no third [option].”A statement asserting that a dichotomy defines the universe of possibilities.” (source: oxfordreference.com, accessed: 28.01.2019). This is because - in my opinion - both positions are equally true. It is because there is an additional variable here - a human being. For some, the advantages of the analogue and the defects of the digital are crucial for a full and satisfying reception of the music, and for others it is exactly the opposite. I hope that you remember the workshops that I hosted during the Audio Video Show in 2017 - at that time I presented the world's first digital recordings released on LP discs (more HERE). You must admit that they sounded insanely good, even if we were talking about 12-bit recordings with a bandwidth of no more than 15,000 kHz. The point is that everything depends on how the disc is prepared - the "vinyl" as such is only a potential option, not a solution to problems. | How is it done: Commonly „vinyl" equals "analog" and vice versa. It is not true, but it makes life easier enough for us to think this way. It should be clear that this is not true, because a vinyl record is only a carrier. The signal recorded on it is analog, but everything that happens before the matrix is cut belongs to the sphere in which everything can happen.

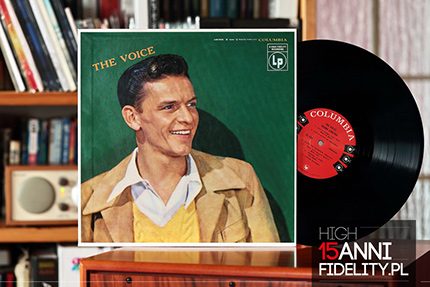

Frank Sinatra’s album The Voice of Frank Sinatra. Released in 1946 on four 78 rpm records, re-released in 1948 but this time on a 10” record – this was the first Columbia’s LP; images shows the Classic Corner 12” re-issue Acoustically | Historically the oldest way was acoustic recording, directly on wax, glass and then also plastic ("acetate") disc; a machine called "lacquer cutting lathe" was used for the recording process. This type of recording is called "direct-to-disc" because the recording takes place directly on the acetate, from which then the matrix is made used to press records. Although in January 1925 a change was introduced to this process - the first electrical recording was made - the principle remained the same. Needless to say, these were mono (single-track) recordings. A tape recorder | It was a simple method, but it had its limitations - the performers first had to focus around one or several tubes, and then around one or several microphones. In addition, the whole song had to be played right away, at the first attempt, with all the instrumentalists and vocalists and it could not be edited, nothing could be added to it. Although it was not known at the time, a seed of change appeared in 1928, when Fritz Pfleumer patented a magnetic tape in Germany, and in 1935 AEG prese It was almost an epic change, because from now on one could record the same track several times, looking for the best performance - this approach is called "take" - choosing it for the album. Still, it was about individual tracks, because the 78 rpm record could not fit more. In fact, this type of music recording started to take on much later. After the Second World War, the Allies - both Americans and Russians - took magnetophones from Germany to their countries and prepared their own tape recorders. In the USA it was a company called Ampex with their Model 200. They presented their device in 1948 - not coincidentally, because exactly at the same time Columbia presented to the world their 12"(30 cm) LP and a rotational speed of 33 1/3 rpm. Both of these solutions were intertwined with each other and we owe them the unbelievable flourishing of music in the 20th century - the tape released artistic creation and facilitated recording, and the LP, also called Long Play, proved to be an ideal carrier of music.

Nagra IV-S tape recorder; photo from Krakow Sonic Society Meeting #94 If we stayed with the direct-to-disc technique, it would be problematic to extend the length of the playback, because without the tape performer would have to play the whole side of a record from the beginning to the end, with appropriate breaks between tracks, etc. And now they could record the same track multiple times, choose the best version ("take") of each of them, cut the tape and glue it so that it contains selected tracks in a desirable order. A production copy was made from the master tape and it was used to cut the acetate, and from it a matrix was created and finally a LP. As you can see, the path from the performer to the ultimate medium has been extended one more time. Multitrack | And it wasn’t last. Only a year later, in 1949, Les Paul divorces his first wife Virginia Webb Paul. Sorry, it is not the point - yes, he divorced his wife, but more importantly, as the first musician (guitarist) in the world, he published multi-track recordings. Technically it was quite a primitive recording, but in terms of concept it was revolutionary - the musician recorded subsequent tracks on the album acetate, then played it and at the same time recorded the next guitar part for the next acetate, using up to eight of these. The multi-track tape recorders appeared on the market in the mid-1950s - Les Paul bought his first tape recorder, the eight-track Ampex in 1957. Thanks to several tracks, he could record additional instruments, improve those recorded, and then mix them and record them on tape - either to one track (mono) or to two tracks (stereo). The master tape thus prepared was copied, a copy was used for ... and so on. It created situations when only the third, fourth and even the fifth copy was actually used for a release. And in analog technology, each copying means an increase in distortion, including noise - each time by 3 dB. Digital | As you can see in the process aimed at making the recording easier and expanding the creative expression (technique and artistic side were equally important in this process), the path from the artist to the media lengthened once again. As it turned out it had its price - deterioration of the quality of the recording. This is why Japanese engineers, and later also American ones, attempted to make digital recordings; The Japanese succeeded in 1971, and the Americans in 1975. Digital recording - first stereo and then multi-track - eliminated the main problems of analog recordings. However, it generated its own with which many music lovers can not "get along" still today. Direct-To-Disc | Those loving sound did not have it easy. All the advantages of multi-track recordings on an analog magnetic tape proved to be a problem for them, not a solution. So they diagnosed the problem very early and proposed a solution: return to the simplest method, that is, to direct-to-dics recordings. It is not known exactly which company was the first, but certainly one of the most important was the American label Sheffield Lab. founded in 1967 by recording engineer Doug Sax.

One of the best Sheffield Lab. releases: Adam Makowicz, The Name Is Makowicz (Ma-kó-vitch) (Sheffield Lab LAB 21, 1983) Of course, the company has its founding myth, because on its website it reads that Doug Sax and his colleague from the Lincoln Mayorga band made the first such attempt in 1959. However, these were experiments - nota bene they cut the 16" 78 rpm record (!). The first commercially recorded direct-to-disc is from 1968, when the gentlemen recorded the Lincoln Mayorga & Distinguished Colleagues (I) album. Today, Doug Sax is considered the "godfather" of this type of recordings. This eminent sound engineer passed away in 2015. Sheffield Lab., despite their great merits, is not the only record label who recorded music in this way. In 1977, the first D2D album from Reference Recordings Guitar and ... was released, and other American companies experimented with it. A separate world of direct-to-disc discs evolved in Japan - and that's where the most of these discs were released. Ultimately, all of them gave way to digital technology. | DIRECT-TO-DICS in 21st century The end of the 1970s was a period of intense search of record companies, that wanted to eliminate the problems of analogue record, or at least minimize them, while still remaining within the analogue world. We owe to this search the popularisation of 180-gram „virgin vinyl" records, DMM technology, i.e. Direct Metal Master, experiments with disc profile, dbx coding and others. It was, however, a swan song of the LP. I mean, it seemed like swan song. It turned out that - sticking to ornithological terminology - the LP was reborn like a phoenix from ashes and flew up, like an eagle :)

„Lathe” Neumann VMS 80 in Emil Berliner Studios. Photo: Emil Berliner Studios Along with the slow return to this medium, they also returned to the techniques from two decades ago, including D2D recordings. Already in 1990 at the Bridges Hall of Music in California, Cardas Records - a separate branch of the cabling company - recorded Kip Dobler's album Reaching Out From The Inside. However, this was an isolated case. More recordings were released in the 2000s, partly thanks to the session that in 2001 at the meeting of the Audio Engineering Convention was prepared by an engineer Robert Auld. A D2D disc was recorded then, which was later listened to and compared to live music together with the participants of this meeting (more HERE). Still these were experiments,, individual actions. In 2007, the Pauler Acustics studio together the Stockfisch Records recorded and released the D2D The Bassface Swing Trio album The Bassface Swing Trio plays Gershwin (review HERE). A year later the Groove Note album Percussion Direct was released, and in 2011, Analogue Production releases a whole series of this type of recordings on 200 g vinyl, recorded at Blue Heaven Studios and cut by Kevin Gray. This technology gained momentum among more and more well-known sound engineers and albums were recorded in more and more prestigious places. For example - in October 2012, the Grammy winner, sound engineer Vance Powell recorded in The Blue Room studio, owned by Jack White, the album by The Kills Live At Third Man Records, using the Rupert Neve 5008 console and Scully lathe from 1953.

Great album – Hilary Hann on two discs – one was recorded using the D2D technology in Emil Berliner Studios, by Rainer Mailard (I’ll get back to him in a moment), the other is a classic digital recording. In the same year, the British company Chasing The Dragon debuted, but it was only their album from 2015 that made some fuss on the market in our, but not only, industry - it was the Big Band Spectacular! album performed by The Syd Lawrence Orchestra, recorded at Air Studios, a London studio founded by George Martin. It was a high-budget venture, and the music lovers received a double album, with one record cut in D2D technique and the other, with the same material recorded in parallel on a 24-track analogue recorder. | THE BERLINER DIRECT-TO-DISC RECORDINGS Three years earlier than Chasing The Dragon, the first D2D album was recorded by the German company Berliner Meister Schallplatten , using the Emil Berliner Studios. It has a direct relationship with the inventor of the turntable and one of the most recognizable record labels in the world, that is the Deutsche Grammophon. It is currently the only publisher in the world that regularly records and releases D2D albums: The Berliner Direct-To-Disc Recordings. |

| Emil Berliner Studios

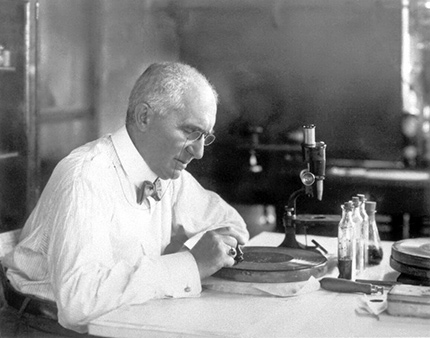

An undated photo of Emil Berliner leaning over an acetate of a vinyl record. Photo: dpa The name 'Emil Berliner Studios' refers to the name of Emil Berliner (1851 - 1929), the inventor of a turntable and vinyl record. Today it is a branch of the Deutsche Grammophon label specializing in recording. In 1898, ten years after the presentation of the turntable, Emil Berliner founded Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft in Hanover, a record label, and in 1900 he moved its headquarters to Berlin. Initially, it was a studio with three rooms. Due to the damage caused by allied air raids during World War II, after 1945, the studio operated from Hanover, using a mobile studio.In 1946, the first tape recordings were made, which was the forerunner of a real revolution. In 1950, the first stereo recording was made, for Deutsche Grammophon, and from 1969 on, in the new studio in Hannover-Langenhagen, multi-track recordings were available. In 1976 the studio, together with Eugene Jochum, prepared the first 16-track opera recording, and Maurizio Pollini made the first digital recording; in 1979, this time with Herbert von Karajan, the first digital multi-track recording was made. In 1996, the recording studio moved to the brand new Emil-Berliner-Haus in Hannover-Langenhagen and a year later changed its name to PolyGram Recording Services. In May 2008, the EBS was bought by an independent company, separating EBS from Deutsche Grammophon. This gave rise to a new company, EBS Productions GmbH & Co. KG. However, it still uses the Emil Berliner Studios name and has positioned itself as an independent production studio for acoustic music. In 2010, they moved from Hanover to Berlin. Since then, the company's studies have been on Köthener Straße, in the center of Berlin, two minutes from Potsdamer Platz. Today, the studio uses three rooms with digital and analogue recording equipment, and also has an analog connection with Meistersaal, a historical concert hall from 1910. Since 2012, direct-to-disc recordings have been made at Emil Berliner Studios, and in August 2017, the Half Speed Vinyl Mastering technology was reactivated using the Neuman VMS 80 lathe. emil-berliner-studios.com The Direct-to-disc technology may seem like a solution to all problems. But is it really? I would like to show you advantages and disadvantages of this technology using the mil Berliner Studios and The Berliner Direct-To-Disc Recordings as an example. The catalog of this label is quite substantial, so I chose only three new titles representing what the company records: piano solo, violin solo and jazz-folk trio. The producers are the owners, gentlemen Rainer Maillard and Stephan Flock - the former cuts acetates and the latter one is the record producer. Some vintage devices are used for recording, but not only them - for example, a DGG tube mixing console is used, as well as a Reverberation Chamber 1 and Josephson C 722 and Sennheiser MHK 20, MHK 30 and MHK 800 microphones. Acetates are cut using Neumann VMS 80 lathe with Neumann SH 74 head and Ortofon Amp GO 741 amplifiers. The records are pressed at Pallas GmbH.  ╢ KATIE MAHAN | Katie Mahan plays Gershwin Berliner Meister Schallplatten BMS 1706 V

Sound | If I had to point out an instrument that benefits from this most uncompromising technology most, then it would probably be a piano. On this record it sounds fast, detailed, dynamically, has an excellent attack, and it is the attack that most often lacks its recordings. Recording by the Berliner Meister Schallplatten, excellent sound production by Mr. Stephan Flock, and finally a great acetate cutting done by Mr. Rainer Millard, all contributed to the unique album. The sound of the piano is dynamic and fast, but it has not been exaggerated with its closeness. The relationships between its dimensions - and this is Steinway D - and the room were captured very well. So we have a clear image of the instrument and nice acoustics around it. Also the tonal balance is precise, neutral, but also very natural - that's just how a piano sounds like in a medium-sized room. Sound quality: 10/10  ╢ RUTH PALMER | Johann Sebastian Bach Berliner Meister Schallplatten BMS 1816 V

Sound | Bach's recordings for solo violin performed by Ruth Palmer were recorded in a large room at Emil Berliner Studios, the so-called Meisterhall. It would seem, therefore, that the sound will be distanced and small. If, however, I hadn’t known the location of the recording, I would have said that it was a recording from a small room, with closely placed microphones. Neither one nor the other - as seen on the picture on the back - is true. The sound of the violin is tangible, close, rich with details and subtleties, with clearly presented performer’s style, type of instrument - all this information was very intense in this recording. There is less reverberation in this recording than, for example, on the Katie Mahan plays Gershwin and it was more about showing how sound is born than how it develops. It offers a palpable, close and dense presentation. The violin, along with the ambiance, occupy a wide listening field, both sideways and backwards. The dynamics is flawless, just like detail level. I'm not a fan of such a close recordings, because they focus listener's attention on the upper midrange, but it's hard to deny that this album accurately presents the "truth" - it's just a violin placed not far from us, slightly enlarged, tangible. But, in my opinion, placed too close to us. Sound quality: 8/10  ╢ JOSCHO STEPHAN TRIO | Paris – Berlin Berliner Meister Schallplatten BMS 1817 V

Sound | The band is placed almost at your fingertips, it is almost really opposite us. Although we know that it is impossible, because it would not fit between the speakers, and this is the space designated here, we have the impression that it really happens. This is due to the absolute "immediacy" of this sound. Its speed is incredible, probably even greater than what we hear from the analog master tape. I do not claim it "for sure" because I would have to compare them, but I believe I'm right. The tone of this recording is quite bright, the sound is open and detailed. There is no brightness, but you can hear immediately that this uniquely open midrange causes "shivers" on the back and supports dynamics. The sustain phase of the bass notes have been somewhat extended, which reminded me of another purist recording, the Charlie Haden's birthday concert released on the The Private Collection album by Naim. Both there, and here the double bass has a lot of mass and does not sound as fast as it should. I understand this approach, it was about more „mass” to the whole recording, which worked, but it has its consequences as the bass occasionally gets a bit „boomy”. Sound quality: 8/10 Kontakt: FLOCK & MAILLARD GbRBrabeckstrasse 121 30539 Hannover | DEUTSCHLAND info@berlinermeisterschallplatten.de berlinermeisterschallplatten.de MADE IN GERMANY | D2D – TRUE OR FALSE The direct-to-disc technique offers the sound engineer incredible options. And at the same time, it limits him extremely. If it was the best possible method of recording music, everyone would use it today, and all reel-to-reel tape recorders would be long gone. However, it is not. Why? I can start philosophically and say that everything we do in audio is just an approximation, not the whole truth. Therefore, any recording technique - whether older or newer - has the some truth in it, but never the whole truth.

Orchestra rehearsal in the Meistersaal. Photo: Emil Berliner Studios Therefore, various techniques - analogue and digital, including D2D, using tape, stereo and multi-track - coexist with each other and each of them brings something unique to them to the music, something characteristic only for them. And we have a choice. So what does the direct-to-disc technique bring to this pool? PLUS | Recordings of this type are incredibly fast and dynamic. Such an attack of sound can not be achieved in any other way, and if it is possible, I am yet to witness it. Even digital recordings in the highest available resolutions, i.e. DSD256 and PCM 32/384, sound a bit slower compared to D2D. It is not even about slowing down, but the sense that with such discs the sound is "here and now" with an emphasis on "now". Thanks to it we are inclined to believe that it is a natural presentation, lively and open. The treble benefit from it, which is no other recordings are so multicolored and natural. Another unique feature of such recordings is imaging. In short, it's very similar to what an analogue tape shows. The D2D vinyl record is the only consumer medium that offers such a homogeneous presentation, in which it is difficult to point out individual "instruments", nothing is emphasized, but we immediately know where which of them is, where the sound comes from and how it differs from reflections. On the other hand, a vinyl record, as well as the best digital recordings, show everything in a more "made" way - more impressive, but still artificial. And in their case, you can talk about the "sound stage" - there is no such need when listening to the "master" tape and D2D discs. MINUS | All D2D discs I know sound slightly bright and light. It's not even about their tonal balance, it is usually good, but the amount of details and subtleties presented in the upper midrange and the treble that focus listener’s attention in these parts of the band. It should be a positive thing, but it not always is. The situation which we are in, that is listening to music at home, played mechanically from a medium, is an artificial situation and requires proper preparation of the material - the D2D sound in a quite "simple" way. I usually also lack some „flash on the bones” in such recordings and some more three-dimensionality - both of these elements are partly artificial, added during the sound processing, but they allow us to listen to music in a more comfortable way.

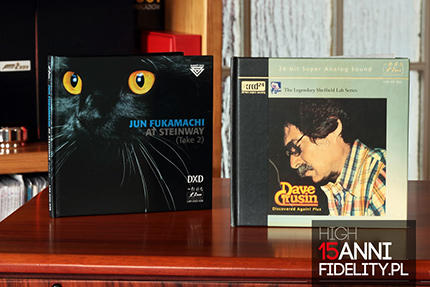

Some D2D recordings were recorded in parallel on a tape - for backup. Today they are released on both vinyl and digital media. On the left a CD recorded directly from the D2D disc (Jun Fukumachi, Jun Fukumachi at Steinway (Take 2), Toshiba-EMI / Lasting Impression Music, LIM DXD 038, silver-CD, 1976/2008), and on the right CD with the material from the backup tape (Dave Grusin, Discovered Again! Plus, Sheffield Lab / Lasting Impression Music LIM XR 002, XRCD24, 1976/2003) And so? | So neither true nor false, rather something in between. It's worth having some of these albums, because listening to them is a unique experience, and the system will present its best performance in terms of dynamics and detail. We will also have a close encounter with the imaging method offered only by high-quality analogue tape. I, however, understand the D2D releases as something "next to" the mainstream,, a kind of specialized "race car". If we want to feel the adrenaline rush - we can reach for a D2D recording. Still, most days I prefer a different type of presentation. In my opinion, analog tape prepared in a studio - it can be a recording straight to two tracks, but also not a very complicated multi-track one - offers more satisfaction and, paradoxically, brings us closer to the emotions associated with the situation in front of microphones. Being a true audiophile, a collector spending a lot (way too much) of money on music, a supporter of simple solutions (you can say "purist"), as well as a specialist who researches everything related to our industry, I turn out to be a supporter something that Brian Eno said once: If you had a sign above every studio door saying ‘This Studio is a Musical Instrument’ it would make such a different approach to recording. Wojciech Pacuła |

About Us |

We cooperate |

Patrons |

|

Our reviewers regularly contribute to “Enjoy the Music.com”, “Positive-Feedback.com”, “HiFiStatement.net” and “Hi-Fi Choice & Home Cinema. Edycja Polska” . "High Fidelity" is a monthly magazine dedicated to high quality sound. It has been published since May 1st, 2004. Up until October 2008, the magazine was called "High Fidelity OnLine", but since November 2008 it has been registered under the new title. "High Fidelity" is an online magazine, i.e. it is only published on the web. For the last few years it has been published both in Polish and in English. Thanks to our English section, the magazine has now a worldwide reach - statistics show that we have readers from almost every country in the world. Once a year, we prepare a printed edition of one of reviews published online. This unique, limited collector's edition is given to the visitors of the Audio Show in Warsaw, Poland, held in November of each year. For years, "High Fidelity" has been cooperating with other audio magazines, including “Enjoy the Music.com” and “Positive-Feedback.com” in the U.S. and “HiFiStatement.net” in Germany. Our reviews have also been published by “6moons.com”. You can contact any of our contributors by clicking his email address on our CONTACT page. |

|

|

f the speech is silver, and silence is gold, in the world of audio, silver would be a digital release, and an analog one would be gold. It’s just that in a real, not literary life, this proverb is of limited value, because without speech we would still pick out tasty termites from the trees and it is the speech and cooperation that allowed us (humans) to create, for example, a button on iPhone and share the knowledge of how to use it.

f the speech is silver, and silence is gold, in the world of audio, silver would be a digital release, and an analog one would be gold. It’s just that in a real, not literary life, this proverb is of limited value, because without speech we would still pick out tasty termites from the trees and it is the speech and cooperation that allowed us (humans) to create, for example, a button on iPhone and share the knowledge of how to use it.