|

MUSIC | REISSUE FRANK SINATRA

Stereo Sound SSVS-017 |

|

MUSIC | REISSUE

Text: WOJCIECH PACUŁA / Translation: Marek Dyba |

|

No 205 June 1, 2021 |

He began his career in the swing era, in Harry James’s and Tommy Dorsey’s bands. In 1942 he left the bands, starting to sing on his own:

In 1943 he signed a contract with COLUMBIA RECORDS, while in 1946 his debut album The Voice of Frank Sinatra was released on four 78 rpm shellac discs. In the early 1950s, in connection with the change in contemporary musical tastes, his popularity decreased so much that the record label decided not to renew the contract (1952). As it appeared later, it was a big mistake. Thanks to starring in the movie From Here to Eternity directed by Fred Zinnemann (1953), a role awarded with an Academy Award and a Golden Globe, he became very popular again. On March 13th, 1953, Sinatra met the deputy director of CAPITOL RECORDS, Alan Livingstone, to sign a seven-year contract. In cooperation with the record label, he managed to produce some of the artistically and sonically best albums in his career. He then collaborated with the best musicians, conductors and producers. Axel Stordahl, who Sinatra recorded his first album for Capitol with, Gordon Jenkins or Billy May, to name a few, were among the most important arrangers who also prepared instrumentation for the artist. However, the most significant person from that group was NELSON RIDDLE, who Sinatra developed a special bond with, even though it did not seem possible at the beginning: Even though Nelson Riddle came with an admirable list of recording credits (including Mona Lisa and Unforgettable for Cole), Sinatra was, at first, reluctant to work with him. ⸜ op. cit., p. 85. Alan Dell, a record producer from Columbia/EMI, recalls that the two artists began to build their mutual relationship during a session held on April 30th, 1953. Livingston used a trick and, instead of Bill May, who had been appointed with Sinatra, he placed Riddle on the podium, saying that the arrangement had been prepared by the former. Sinatra had never seen Nelson before, so he started to sing. After the song I’ve Got the World on a String was recorded, it became apparent that the two people – Sinatra and Riddle – had developed a special bond. As witnesses claim, Sinatra referred to the experience as “Beautiful!”, which was an exceptional honor and an extreme rarity on is part.

The last album recorded by Sinatra for Columbia Records was Nice’n’Easy which reached the top of the Billboard chart in October 1960. At the time, Sinatra had already been in disagreement with Livingstone for six months. Having decided to start a new chapter in his life, he first wanted to buy Verve Records to record music there, but ultimately he set up his own record label – REPRISE RECORDS. Bound with Capitol by an existing contract, already running his own record label, he recorded five more albums for the former one. Finally, however, he started everything anew, on his own. ▌ SINATRA’S SINATRA ONE OF THE INVALUABLE ADVANTAGES of being part of Capitol Records was the possibility to record at the label’s studios located in the futuristic Capitol Records Building (Sinatra’s session of January 1956 marked its opening). Reprise Records did not have such freedom, as it did not own a studio. Moreover, the death of the sound engineer Morty Palitz (ex-Columbia), who had been Sinatra’s friend, left Sinatra without co-workers. Desperate, in his search he met an independent producer, BILL PUTNAM, the owner of two studios: UNITED STUDIOS and WESTERN RECORDING, located at the Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles. The two quickly got to like each other and started cooperating closely – closely enough for Reprise offices to be located in the United Recording building. Putnam was known for his cooperation with Count Basie and Duke Ellington, as well as respected in his industry. His A and B studios were excellent. Let us add that Putnam was also a constructor who built audio devices bearing the logos of United Audio and UREI.

ALLEN SIDES, the owner of Ocean Way Studios, located at the same place as United Recording, recalls:

It is an important remark, as almost all Sinatra’s albums were recorded with the instruments and vocalist placed in one room. In the 1960s, studios would normally isolate a singer from the orchestra, recording the former onto the third track of a three-track tape recorder, to be able to balance the vocal well during the mix. However, Sinatra liked to feel music. Besides, each recording session took place with an audience, which additionally stirred him. So, he would face the orchestra, standing behind the conductor, sometimes only with an acoustic panel behind him. Most Sinatra’s records from the times of Reprise Records were made at Studio A, i.e. the largest one, while only a few were recorded at the more intimate Studio 1 and Studio 2, located further away on the same street. Let us add that the standard procedure then was to record many attempts that were sometimes edited together to form one track and sometimes released on the following reissues. So, such subsequent reissues, despite no apparent differences between them, give us slightly different versions of the same tracks. The “Stereo Sound” version seems to be compatible with the reissue from the year 2014. However, Phil Ramone, Sinatra’s producer, says that two or three attempts were enough for Sinatra – more wouldn’t have made sense. The artist was used to recording three tracks during a given session and finalizing a whole album in four days (Granata, p. 161). Compared to months of work needed by other artists, it was a unique approach, typical for the times when one relied on making the recording as good as possible, not on production.

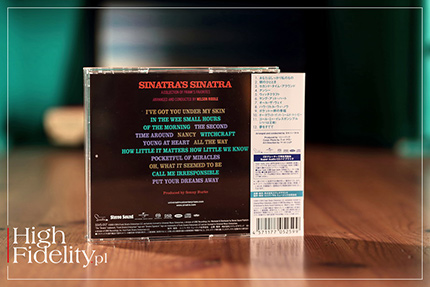

In the 1960s, when Sinatra was really popular, both record labels that he had previously cooperated with, i.e. Columbia Records and Capitol Records, issued compilations with his best songs that would sell quite well. Sinatra decided to make use of that and recorded ten of his older songs again, adding two new ones: Pocketful of Miracles and Call Me Irresponsible. Nelson Riddle was in charge of the arrangement and conducting the orchestra. The new SACD edition features a booklet in which we can read that:

⸜ RECORDING STEVE ALBIN, who has provided us with probably the most detailed discography of the artist, points out, with reference to the albums from Reprise times, that the first track to be included on it later was Pocketful Of Miracles by Sammy Cahn and Jimmy Van Heusen (No. 634 in the record label’s catalogue). It was recorded on November 22nd 1961 (!) at United Recorders, and the conductor was Don Costa, not Riddle. Three out of the five songs recorded at the time were released in 1962 on Sinatra & Strings. So, today we would refer to them as a “discard” from a session :) |

The next track, Call Me Irresponsible, was recorded on January 21st 1963 (b. 1672-4) in Los Angeles, but it is not know exactly at which studio – United Studios or Western Recording. However, the conductor was Nelson Riddle himself. Finally, on April 23rd 1963, again at United Records, the main part of Sinatra’s Sinatra was recorded: five tracks altogether, though four were a standard (more details: Frank Sinatra Discography. The Reprise Years, JAZZDISCOGRAPHY.com, November 21st 2018, date of access: 27.04.2021). The album Sinatra’s Sinatra was issued in the same year as The Concert Sinatra, arranged by Riddle for an orchestra consisting of 76 musicians. In the first years of Reprise Records, it was striking how super-relaxed the atmosphere at the studio was during recording sessions – in the end, Reprise was founded as a “home” for artists and their freedom, which can be heard in extra records added to digital album reissues, where one can also hear conversations between tracks. ⸜ TECHNOLOGY It is clear, however, that the days of Sinatra’s sonically best albums (from the times of Columbia Records) were over. Nobody, including Sinatra’s biographer cited here (Granata), has been able to answer this question. It may have been caused by stress connected with how busy the studio was and thus shifting emphasis from recording to mix and mastering. Anyway, Sinatra’s Sinatra, the 39th album in the artist’s career, is one of his best recorded albums from that period.

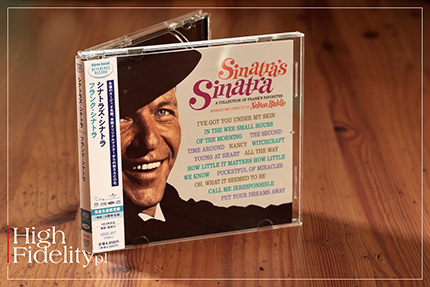

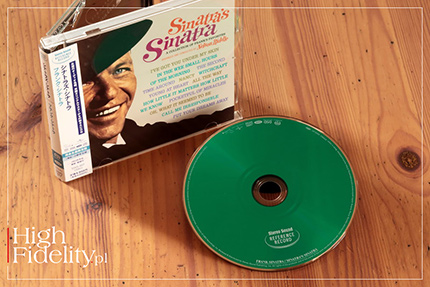

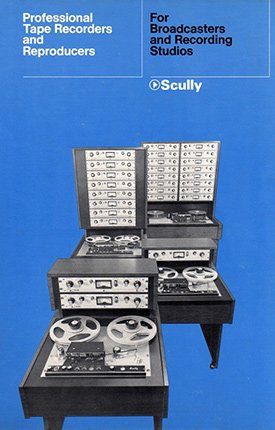

Putnam’s studios were equipped with mixing consoles that he had made himself. It is known that until 1962 he had been using a three-track Ampex tube tape recorder, while afterwards he bought an additional four-track solid-state Scully 280-4 tape recorder. Both devices featured germanium transistors and, in 1970s, they were used to make amazing records by OKIHIKO SUGANO, the editor of “Stereo Sound” (more HERE). The Ampex device recorded material for monophonic, while Scully – for stereophonic mix. Sometimes, like in the case of September of My Years, some of the material was recorded with the former and some with the latter (more information available on STEVE HOFFMAN’S: portal; date of access: 16.04.2021). ⸜ THE ISSUE The album in question was issued by Stereo Sound Publishing Inc., the publisher of the Japanese quarterly “Stereo Sound”. The magazine has been releasing CDs and SACDs for a long time. It started with samplers, but has also been including reissues for the last few years, the most important of which has been a version of Bach’s The Goldberg Variations played by Glen Gould (price: 7,000PLN!), released on a Glass CD [SGCD02 (TDCD91228)]. Apart from the exceptional glass material used, another distinguishing feature of the disc is its turquoise lacquer color. This solution was originally developed for SHM-SACDs and Platinum SHM-CDs, and it is designed to reduce the number of reading errors caused by dispersed light of the laser reflected from metal. In the case of SACDs, sonic improvement can also be obtained while omitting the CD layer. It is because hybrid SACDs/CDs are made out of two separate discs, which affects their mechanical integrity. In such a way, i.e. with separate SACDs and CDs, “Stereo Sound” released a whole series of reissues, among others Sinatra at the Sands (2009). In last year’s “Winter” issue, information was published on new titles with the logo of the magazine (2021, Winter, No. 217). Next to classical music, there were also three Frank Sinatra’s albums: It Might As Well Be Swing recorded with Count Basie, the 50th premiere anniversary version of My Way and Sinatra’s Sinatra.

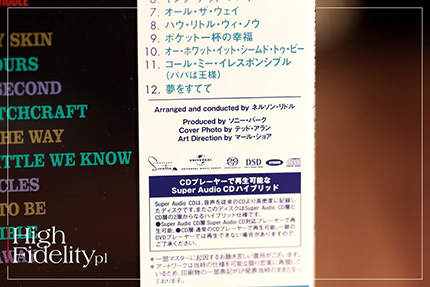

The albums were released in classic jewel boxes with an obi, in the form of hybrid SACDs/CDs. The information given on the obi suggests that the issue is based on material recorded in high resolution (probably 24/96 PCM). Material for the “Stereo Sound” issue was remastered anew, so “flat-master” files were probably used, copied without corrections from master tapes in 2014, when Universal Music Enterprises (UME) issued remastered versions of Sinatra’s albums as part of the “Signature Sinatra” series. This time, the person in charge of remastering was KOJI “C-CHAN” SUZUKI (Kouji Suzuki Kohji Suzuki) who works for Sony Music Studios in Tokyo, while Hajime Someya from “Stereo Sound” was responsible for production. Acknowledgements include LARRY WALSH who had remastered the “Signature Sinatra” series, as well as the earlier Capitol Records reissues. Let us add that Walsh is one of the best remastering specialists to have dealt with Sinatra’s albums. “Stereo Sound” SACDs are released as part of the “Signature Sinatra” series specially created for the purpose, while the essay accompanying the issue reviewed here was written by Koji Onodera, one of the journalists working for the magazine. It is just the fourth digital version of the album (the first one was released in 1991) and, at the same time, the first one issued on a SACD. ▌ OUR LISTENING SESSION The way we listened For the purpose of the comparison, I used the 2014 CD reissue of Sinatra’s Sinatra. Additionally, I also compared the album Sinatra at the Sands, issued by “Stereo Sound” in 2009, with its earlier reissues. I also listened to the 2010 CD reissues of other Sinatra’s albums, as well as LP and SACD Mobile Fidelity reissues. The SACDs were played on the SACD Ayon Audio CD-35 HF Edition player, while the LPs on the Pear Audio Blue Kid Thomas turntable with the Cornet 2 arm and Miyajima Laboratory Madake cartridge.

FRANK SINATRA’S ALBUM REISSUES have a long history, as already his debut album from the year 1946 was first released on a 78 rpm vinyl disc and then issued in the then new Long Play 33 1/3 rpm format. Its later reissues were even more interesting, as they often featured different mixes and other track versions, sometimes with a reversed stereo panorama. The majority of the reissues were released on LPs and later also on CDs, while SACD versions have only been offered by the Mobile Fidelity record label. However, the 2009 issue of Sinatra at the Sands brought yet another perspective on the material. That was when it was reissued under the auspices of the Japanese “Stereo Sound” magazine, one of the most important audio magazines in Asia (and not only Asia). The reissue was untypical, as it consisted of two discs – DSD signal was transcoded from high-resolution PCM files onto a one-layer SACD, while a PCM remaster was released on a CD. I compared it to a SHM-CD issue from the same year, released by Universal Music Japan as No. 5 in a series. The difference is striking – the SHM-CD sounds bright and noisy (when compared to the other version). Its sound is selective, but the resolution is not higher. Once heard, the “Stereo Sound” issue becomes THE RIGHT ONE. Even though Sinatra’s Sinatra is a hybrid, it goes even further. Its sound is warm and dense. The volume of the vocal is finally large and intimately “present”, but also placed far away enough from listeners, so as not to overwhelm them. Strings, usually bright and recorded in a way that locates them at a different bandwidth than the vocal, have also reached an outstanding level here, but without the noise. Even the harp at the end of Young at Heart has a nice and dense tone color, and warm sound.

There is also strong, surprisingly low bass, which is not that typical for Sinatra’s albums. To discover it, you need to listen to the double bass at the beginning of How Little it Matters How Little We Know, or, even more, the extremely low sound of Pocketful of Miracles. So, the musical message is founded on a strong base and it is finely seated on dense bass and low midrange. This adds magnitude to the panorama that nicely extends to the sides, but also has great depth. However, above all, the most enchanting feature is Sinatra’s vocal itself – it is large, warm and dense. It is not brightened up at all, so the sibilants are only an accompanying element, not its distinguishing feature. Despite the overall warm sound, the percussion plates are clear and strong, just like the brass instruments. Reverberation added to individual sections is also clear, but none of the elements dominate or impose their presence. It is, ultimately, a warm version – and it is good the way it is. It features a successful combination of a large band with the intimacy of the vocal, which is a great solution in Sinatra’s case, an excellent interpretation of the recording. There is some kind of inner smoothness and coherence within it, while all the sub-bands are perfectly harmonized, resulting in a beautiful whole. ▌ CONCLUSIONS MATERIAL INCLUDED ON SINATRA’S ALBUMS released by “Stereo Sound” is almost certainly transcoded from hi-res PCM files. In comparison, the purist recording of analog master tapes onto DSF (DSD) files done by Mobile Fidelity seems better. However, it is enough to quickly compare the MoFi and “Stereo Sound” issues in order to conclude that although it is hard to say which of the approaches is the right one, the latter offer something that each Sinatra’s fan dreams of: warmth, density and high dynamics. They are simply a must-have and all other issues can be put aside. ■ |

HERE HAVE NOT BEEN MANY PERFORMERS in the history of popular music who are as vocally recognizable as Francis Albert Sinatra, i.e. FRANK SINATRA. Born on December 12th, 1915, in New York, a descendant of Italian immigrants, he never learnt to read notes. His hard work and charisma paid off, as he quickly became an important figure in the music industry, President Kennedy’s friend, a real VIP. He was an unquestionable leader and perfectionist at the recording studio. However, his life resembled a rollercoaster with effective ups and equally quick downs, though finally he reached a level inaccessible for other crooners.

HERE HAVE NOT BEEN MANY PERFORMERS in the history of popular music who are as vocally recognizable as Francis Albert Sinatra, i.e. FRANK SINATRA. Born on December 12th, 1915, in New York, a descendant of Italian immigrants, he never learnt to read notes. His hard work and charisma paid off, as he quickly became an important figure in the music industry, President Kennedy’s friend, a real VIP. He was an unquestionable leader and perfectionist at the recording studio. However, his life resembled a rollercoaster with effective ups and equally quick downs, though finally he reached a level inaccessible for other crooners. WRealizing there was a place for the romantic musical style he was leaning toward, (he) set out to perfect a musical persona to fit the bill: positioning himself not just as a multi-talented creative artist, but a commercial one as well.

WRealizing there was a place for the romantic musical style he was leaning toward, (he) set out to perfect a musical persona to fit the bill: positioning himself not just as a multi-talented creative artist, but a commercial one as well.